The Heresy of Christian Buddhism

Modern Christianity has become infected with Buddhist ideas

This is a guest essay by the Australian Catholic blogger The Social Pathologist - Aaron.

You are My friends if you do what I command you. No longer do I call you slaves, for the slave does not know what his master is doing; but I have called you friends, because all things that I have heard from My Father I have made known to you. You did not choose Me but I chose you, and appointed you that you would go and bear fruit - John 15:14-16

And God saw all that He had made, and behold, it was very good. And there was evening and there was morning, the sixth day - Genesis 1:31

No Christian, looking at the state of Christianity in the West today, can be happy with how things are going. Everywhere where one looks, one is struck by the withering of once all powerful faith that both united—and divided—its constituent peoples. How did a faith, whose importance to men was so central their being that it motivated them to heroic efforts of self sacrifice, piety, artistic genius and even cruelty over points of definition, atrophy to the extent that it has become largely irrelevant in public life? So much has the status of Christianity declined that it is now seen by the majority of the people in the West as a public nuisance.

The standard conservative reply to the decline of the faith is to put the blame on Liberalism and Modernity, and it’s quite understandable how one can arrive at this conclusion. Yet, despite being able to identify the disease, the question that never does get raised is why conservative Christianity been unable to mount a successful opposition.

I would argue that this inability to mount an effective resistance against liberal Christianity points to a problem within modern “conservative” Christianity itself. My main area of interest is the relationship of Catholicism to modernity, particularly with regard to its inability to reverse the secularisation of European culture. However, the more I have looked into this problem the more I have realised that this is a problem which affects Protestantism as well, and its causative elements transcend traditional religious divisions. As I see it, both faiths have gradually drifted away from a fundamental understanding of the self, the created world and the relationship to God. Both faiths are are slowly transforming into a Christian versions of Buddhism.

What I mean by the notion of Christian Buddhism is the transformation of the Christian world view into the Buddhist one, albeit with Christian “dressing.” This transformation has largely been driven by “conservatives” hoping to stem the de-Christianisation of the West. What I wish to emphasise is that this transformation is primarily occurring in “conservative” Christian circles and is distinct from the decay that Liberalism brings. In effect Christianity is caught in a pincer grip between the vices of Liberalism and the Buddhism of “conservatism.”

The traditional Christian understanding of the relationship of Man, God and nature was that the created order was good. In the Genesis narrative, Man, when created, lived in peace with God were he was blissful until he sinned. Sin corrupted this state of affairs, but it was sin, and not the natural order which was the problem. In God’s design, Man and the created order are meant to be symbiotic and not oppositional and noted in John above, the relationship between man and God was one of friendship, neither incorporation or subordination. Man, in his state of Grace was unique and distinct from the God who loved him.

Buddhism on, on the other hand, saw the man’s relationship with the natural world as being problematic and the intrinsic relationship was as one of pain (Dukkha). Happiness, Nirvana, was achieved through a process of detachment from the world since the love or “grasping” of anything would eventually lead to suffering. Through a process of detachment from the world, the self is extinguished (Annata) and man exists in a state of emptiness and universal interdependence (Sunyata) where he is one with everything. Peace and happiness is achieved through union and incorporation into the universal reality. The happiness of man is dependent on his indistinction and escape from the natural world. The process of “spiritual development” in Buddhism resulted in stoic acceptance of things, even a fatalism. Letting go of all things, even the things we love, was the way of Buddha. The Buddha is meant to have said that all life is suffering, the solution therefore was to abandon life.

It’s worth remembering that when European Christians first encountered Buddhism they looked upon it with horror, seeing it as a nihilistic religion. What do we mean by nihilistic, since the term seems to have so many different meanings given the context in which it used? Very briefly, it denied the notion of the self, it willed the annihilation of personality and identity, and it discounted the value of the created physical world.

The European interpretation of the Buddhist concept of suffering was permeated by its understanding of rebirth and karma, the doctrines that were viewed with horror, as an outrageous nonsense, as fatalism, as fearful doctrines. For example, in 1866 a student of E. Burnouf, Barthélemy St Hilaire argued that “the Buddhists have so monstrously exaggerated the idea of transmigration that the human personality is lost sight of and confounded with the lowest things on earth” This aesthetic distaste for the doctrine of rebirth and karma had its teological roots deep in the Judeo-Christian tradition.

That is why the religion of optimism – Christianity – was effectively contrasted with the philosophy of pessimism – Buddhism. And, as Philip Almond has rightly remarked, “it was because pessimism itself was the dark side of the general façade of optimism that the ninetheenth century has erected.” Treatment of the Buddhist soteriological concept nirvana as annihilation of the individual, the final extinction of personality clearly reflected such attitude. For theistic and positivist Europe, it was extremely puzzling why a religion which in other respects was so admirable should have as its summum bonum such an apparently negative aim.

- Audrius Beinorius, “Buddhism in the Early European Imagination: A Historical Perspective”

Now what many people may not be aware of is that Christianity has always had its own “in house” crypto-Buddhists, men who interpret Christianity in such a way that it repudiates its foundational propositions. Since Christianity taught that the created order was good, it interpreted the teachings of Christ in such a way that would reconcile the spiritual teachings with the created world. In other words, it sought a balance. The problem with this balancing act is that error can occur with miscalculation.

The point is that error can occur both ways, and while many men can easily recognise the moral evil of debauchery and worldliness, not many see the danger of an ascetic puritanism that pushes too far. Too much emphasis on sin, too much emphasis on humility, too much emphasis on heaven and even too much emphasis on Christ to the exclusion of man soon leads to a Christianity that hates the individual, individuation and the created world. Christianity starts to resemble Buddhism.

A change of emphasis here, a neglect of inconvenient Scripture there, and soon a religion takes a shape that, though difficult to distinguish from the Christianity of the Gospels, somehow has a quite different effect. Pantheism and universalism, for instance, are the heretical exaggerations of feminine attitudes, but how far can one go in stressing the immanence of God and his will to save before Christianity is left behind? When does bridal receptivity become passivity, and when does passivity become Quietism? There have been differences of opinion over where to draw the line. The authorities win in the textbooks, but the mystics have often won the battle for popular influence.

- Leon Podles, The Church Impotent

Christianity has always been battling against fleshy corruption but its most dangerous enemies have been ascetic. A whore is easily identified as a whore but a hyper-pious “Christian” is less likely identified as a Buddhist. Therein lays the danger. Error can spread throughout the faith cloaked in an apparent piety which it makes it difficult to diagnose and purge.

Value the world too much and the religion becomes carnal and degenerate, value the spirit too much and it becomes abstract, platonic and self-destructive. Purity and reform movements, in reaction, are particularly prone to embracing an ascetic ideal which pushes too hard, and re-evaluates, in the negative, human nature and the created world. Wash dirty clothes and they become clean but wash them too much they become bleached. The aim is to wash the sin away from man and not bleach human nature.

Since everyone imagines the Devil as a libertine, no one imagines him as a Puritan - and that’s how error creeps in. Men who fast, spend hours in prayer and deny themselves pleasures are instinctively felt to be holy men, but holiness is living rightly in the eyes of God and not trying to outdo Christ in suffering and denial. There is such a thing as wrong kind of purity and these men who have been Christianity’s most dangerous opponents. In the early days of Christianity it was the Manichean philosophy that expressed this sentiment but it is a philosophy that resurfaces at different times and in different forms. What keeps the heresies resurfacing is the reapplication of the wrong kind of purity. A purity that sees man, his pleasures and the created order as inherently wicked.

And so it was in the thirteenth century, when the obvious danger outside was in the revolution of the Albigensians; but the potential danger inside was in the very traditionalism of the Augustinians. For the Augustinians derived only from Augustine, and Augustine derived partly from Plato, and Plato was right, but not quite right. It is a mathematical fact that if a line be not perfectly directed towards a point, it will actually go further away from it as it comes nearer to it. After a thousand years of extension, the miscalculation of Platonism had come very near to, a rebirth of Manicheanism. [emphasis added]

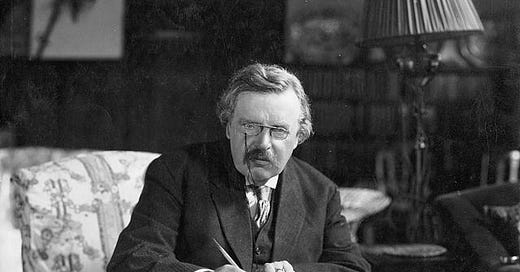

- G.K. Chesterton, St. Thomas Aquinas

Christianity has always had its crypto Buddhists but they have been checked through a variety of mechanisms in history. However modernity has caused a crisis within the Christian faith and in the effort to combat modernity, these men have assumed dominance. As mentioned before contemporary times the Buddhist approach to Christianity is strongest in some of the neo-Orthodox reactionary movements against Liberalism, in the type of people we think as “conservative”.

As my interest is in Catholic theology, Hans Uhrs von Balthasar stands out as a exemplary representative of neo-Buddhism. My knowledge of Protestant theologians is far more limited, but Karl Barth drifts along the same lines and there is a strong Protestant Kenotic theology of that arose in 19th Century Germany that echos the same themes. Both Barth and Balthasar are considered orthodox theologians and both were hugely influential in the 20th century Christianity. Balthasar particularly was lauded by John Paul the second and Benedict, popes considered orthodox. Both were exponents of kenotic theology and both drifted from the traditional Christian understanding of the subject.

Kenosis theology—or the theology of self-emptying—is based upon Phil 2:6-7 where Christ emptied himself of “something” to become man. Traditionally, the kenotic mechanism was felt to be related to the process of incarnation however later theologians have turned it into a central idea of modern Christianity whereby man emulates Christ, and through the process of “emptying” is humiliated - and yet, by being humble, lowly, small, poor and weak is lauded and gloried by God. Ergo since man is to walk following the footsteps of Christ he too should aim to be “emptied” in order to receive God’s approval. The essential idea is that weakness, lack of assertion and debasement are pleasing to God and are the ideals of the Christian life. It’s very easy to see how this doctrine is closely related to the the doctrine of Sunyata—self emptying—in Buddhism.

Remember, this is not being taught by the liberals but by the ‘conservative” Christians.

It’s then very easy to see how any form of assertion, strength, self-improvement or force would be seen negatively in this kenotic schema, and it’s no surprise that traditional masculinity with its close association to the former attributes would be foreign to this line of thought. Many commentators have spoken of the apparent feminisation of Christianity but they have noted are the effects and not the cause, since what we’re are actually observing is the “Buddhisation” of Christianity resulting in the worship of God in an apparently feminine submissive mode. By its influence, Christianity becomes a celebration of self-abasement, non-resistance and pathological altruism, where sensible actions to preserve the self and assert the truth of Christianity are seen negatively.

Suffering and poverty, with its link to self-emptying, become positively evaluated in this schema and thereby the joys of this life are seen as impediments to personal sanctification, a Christian version of Dukkah. The glories of Christianity are glossed over but faults, perceived or imagined, are the focus of attention.

And finally, since distinction is essential to the notion of identity, Christian Buddhism loses value of particular in preference to the universal and is in fact hostile to any “clinging” to the particularities which confer distinction. Instead of celebrating the differences between peoples, localities and nations it aims towards a universalisation and homogenisation.

Christian Buddhism also changes the relationship between God and man. The hostility with which Christian Buddhists evaluate man leads a hyper-evaluation of the identity of Christ with respect to man. Barth was repeatedly and credibly accused of Christomonism (Christ is everything). Christ becomes everything and man nothing and instead of being related to each other as friends, as spoken by the mouth of God in scripture, man’s relationship to Christ is recast as one between master and submissive which has a close analogy to erotic love. Men start to worship God like a woman instead of worshipping like men. What I mean by this is that as men, under the Buddhist schema we don’t worship God as men of honour, where our worship of God is a duty. Instead we worship God as an emotional experience. Once again Christianity becomes apparently feminised.

As I see it, the drift to Christian Buddhism is due to a multitude of influential factors. Much like pacifism, Christian buddhism relies on turning a blind eye or “explaining away” problematic scriptural texts which don’t conform to innate cognitive biases and sentiments. For some strange reason men are more easily disgusted by debauchery and excess rather than by life denying asceticism and pain.

And yet both sin.

Recognising the phenomenon of Christian Buddhism helps us understand the collapse of the faith in the West. Men pay lip service to the notion of Grace but no man comes to God except by it. It’s easy to see how God could be disgusted with Liberals and withdraw His Grace from them, but what’s harder to recognise, and what I increasingly think is fact, is that God may not be too pleased with the new “Christian” Conservatives with their crypto-Buddhist theology, as is withdrawing Grace from their flocks. As I see it, I see it Christianity is caught in death grip between Leftward and Rightward versions of error.

The task before us is not how to “remasculinise” the Church but how to “de-Buddhist” it. With God’s approval his Grace will lead men back to it, no matter what barriers are put forth. How this plays out not one knows but Christ promised us that the Gates of Hell will not prevail against His Kingdom.

I live in Hope.

I believe in the Word.

There's a strong element of this in current Reformed (Calvinist) churches: the idea that the world is totally fallen and corrupt, but temporary and totally unimportant anyway, and Christians should not concern themselves with politics, art, science, civic life, neighborhood, but seclude themselves with Children, Cooking, and Church, prayer being the primary weapon for everything, not action. It's a kind of inconsistent monasticism, since in practice we don't spend hours in prayer and worship, though we do spend hours on church activities like bible study, meetings, and church work days.

To get the other side of it, Catholic philosopher Max Scheler approaches the root of Buddhist-like elements in 19th Century German Protestantism. The easiest primer to his approach is probably his book, Ressentiment, in which he argues that the root of Buddhist thought in Christian societies is the rise of the bourgeois class whose particular psychological characteristics (as described by Weber, for example) made them vulnerable to axiological deformations typified by ressentiment and scheelsucht (envious value-inversion and propensity to disparage the good out of spite).

The tendency to reduce Christianity to a mere moral code justified by airy religious reasoning permits the world-contextualizing passages to be reformed as world-denying passages, which better fits with the tendency of the anti-agonistic and anti-physical bourgeois personality. Remember that the bourgeois archetype of the 19th C. is someone like Howard Taft - proudly obese, anti-physical, and intellectual. Despite the reputation of the bourgeois as hypercompetitive, in reality the highest virtue of bourgeois society was comfort and pleasure, of securing wealth and passing it to one's children. The robber-barons were the tails of the curve, not the median.

Resentful of the very physical and agonistic aristocracy, and filled with self-hatred at the unaesthetic and diseased life they lived, the bourgeois naturally adapted a Buddhist Christianity to themselves. The Will of God is replaced by democratic ultramontanism, love with Social Gospel politics (explicitly in the case of Richard Ely), and the Christian mind-body fusionism with a mind-body dichotomy justifying the neglect of the physical in ourselves.

I recommend Scheler's Ressentiment for further reading on this topic. He manages to incorporate and correct Nietzsche on this topic, which is a profound accomplishment in itself.