The Logic of Ditching Broken Institutions

The strategic dilemmas driving us to exit rather than reform

I’m pulled in two different directions on institutions. On the one hand, we need institutions badly. On the other, our institutions are functioning poorly, and most of us have no ability to affect them.

There’s a game theory puzzle called the Prisoner’s Dilemma that helps explain this. Two criminals are being held by the police in separate cells. If neither of them talks, they both get off with a light sentence. If one of them talks, but the other does not, then the one who talks gets off completely while the other gets a heavy sentence. If they both talk, then they both get a moderate sentence.

Though both criminals are better off if neither talks, the only logical move for both of them is to confess. Thus both of them end up with a heavier sentence than if they’d both stayed silent.

While not exactly the same, there’s a sort of analogous logic regarding institutions. We’re all better off with strong, well functioning institutions. To create and sustain that would require participation and investment from most of society. But given the state of all too many of our institutions, the only logical move for many people is to abandon them, or take some other negative stance such as exploiting them, attacking them, etc.

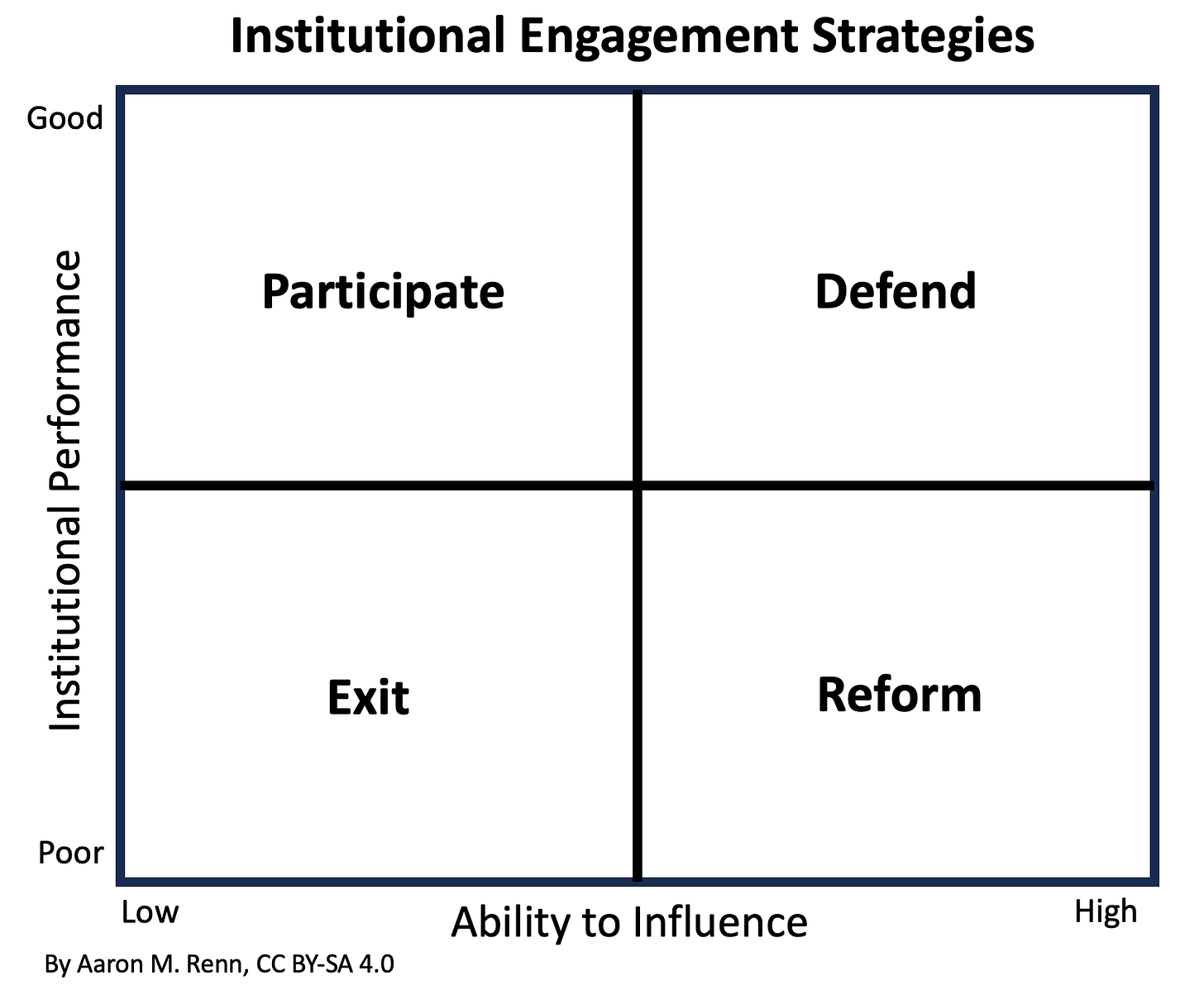

We can model institutional engagement with this matrix. It has institutional performance on one axis, and the ability to influence an institution on the other. This leads to four separate strategies: Defend, Participate, Reform, and Exit.

Defend. For those institutions that are high performing, and where a person has a high ability to influence the institution, the logical strategy is to try to defend the integrity of the institution to preserve and enhance it as a high functioning part of society.

Participate. In those cases where the institution is high performing, but a person has limited or no ability to influence it, the strategy is to participate in the institution. Stay engaged, but don’t make any attempts at change or influence.

Reform. Where an institution is functioning poorly, and a person has a high ability to influence it, one logical strategy is to try to reform the institution, to fix it so that it becomes high performing.

Exit. When an institution is functioning poorly, and a person has a limited or no ability to influence it, the logical strategy is to exit or abandon the institution if possible.

Obviously, there’s a continuum here. It’s not always obvious what institutional performance is good or bad enough, or how much ability to influence is high enough or not high enough. But this gives a basic overview.

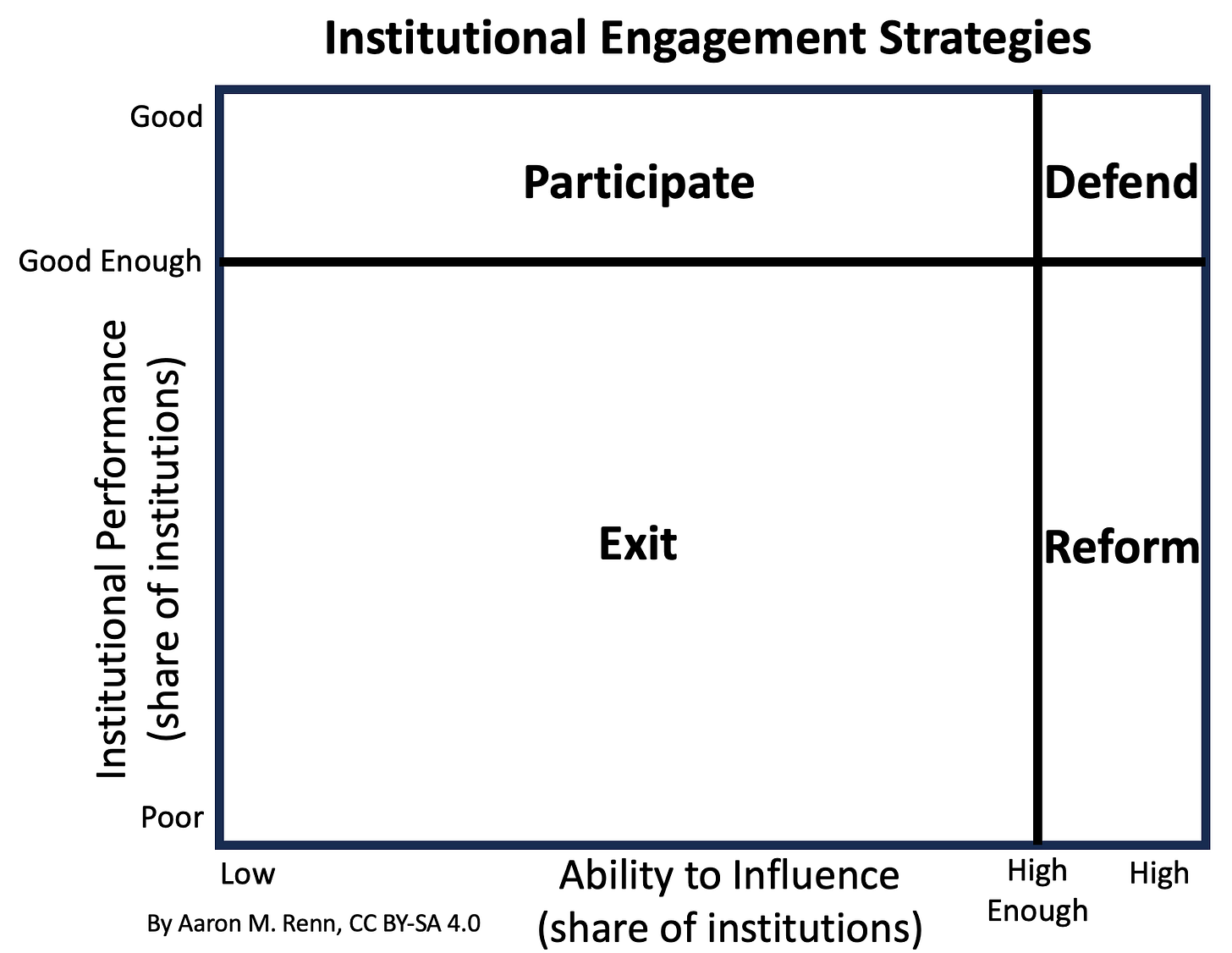

While this matrix shows institutional engagement strategies, it also shows the boxes as equal sized. But there aren’t equal numbers of institutions in each of them.

Realistically, most people have very little ability to influence the bulk of the institutions in their lives. And I think there’s a widely shared belief that many of our institutions have serious problems. How many fall into that category, which ones they are, and for what reasons are all subjects of debate. But people seem to agree that we have a problem.

If we scale the axes based on this, we get more proportional sizing. Here’s an illustrative version.

For most people in a large share of cases, the rational move is Exit. This goes along with Albert Hirschman’s (author of Exit, Voice, and Loyalty) observation that Exit has a privileged position in American culture. We see Exit in the case of public schools. Many people have abandoned them in favor of home schooling or private schooling.

So we’re in a scenario where we need institutions, but the only logical move for most people is to turn their backs on them.

I’d like to find a way to regenerate our institutions but recognize that I - and most of you - can’t do anything about most of them. So my own writing tends to be pulled in multiple directions on this.

As with my matrix, perhaps the best approach the average American can take is institutional triage. Try to defend and actively participate in high functioning institutions - which still exist in large numbers, thankfully - while exiting from poorly performing institutions where you can, and generally seeking to insulate yourself from the consequences of institutional failure.

This doesn’t necessarily move society in a better direction, as with the Prisoner’s Dilemma, it’s the logical move for the average person.

My model also sheds light on the approach being used by President Trump’s DOGE initiative (Department of Government Efficiency).

Zooming in on my Reform quadrant, we can see that there are times when people have a lot of influence over an institution, but not enough to successfully reform it.

We see this again in our public schools. Poorly performing urban districts have proven stubbornly resistant to reform, even though there are elected officials who theoretically control the schools and are very motivated to improve them.

So what the bipartisan education reform movement did was to start supporting charter schools. They used their influence in order to build exit ramps out of the mainstream public schools into an alternative institution set. In Republican states this has gone even further with the “fund students not systems” model in which families can take their state education funds to private schools as well. Both Democrats and Republicans have been using their influence over educational institutions to incrementally dismantle them.

In the case of the Trump administration and DOGE, he faces a federal bureaucracy staffed almost entirely by Democrats and which is implacably hostile to his agenda. This is not an auspicious environment for reform. It doesn’t seem very likely that the bureaucrats are going to start marching to a different tune just because the politically appointed leadership tells them to. It’s much more likely that they would use every tool in their arsenal to actively resist or delay.

In this sort of environment, there’s strategic logic to the idea of using institutional influence to simply terminate or downsize the institution in question.

Consider the US Agency for Global Media, which runs Voice of America. Just as one example, during the 2020 campaign, while Trump was actually still President and his appointee was in charge of the agency, it ran what can only be described as a get out the vote campaign ad for Joe Biden. You can watch it for yourself in this Politico piece. (When Biden took office, he reversed the disciplinary actions against the people involved and actually rewarded some of them).

Michael Pack, Trump’s appointee to run the US Agency for Global Media, wrote about this as part of an op-ed describing his experience, in which it proved to be impossible for him to actually direct the agency.

This time around, the Trump admin took a different approach. He ordered Voice of America shut down. All of his moves will be litigated to the nth degree. But it’s much more likely that Trump will succeed at shutting things down than reforming them.

Undoubtedly this strategy throws away a lot of good with the bad. But that’s a reason why leaders shouldn’t allow their institutions to become subverted or politicized.

If you’re the one who planted the tares in the first place, then you’re not in a position to complain when a lot of wheat gets thrown out along with them.

Put this all together, and we can see why things continue to trend in the wrong direction when it comes to our institutions. Game theory type logic encourages people to defect from institutions. And all too many of our institutions appear to be impervious to reform efforts, making destroy or deletgitimize an attractive option.

I am on record as saying we need an institutional refresh or reset. But how do we accomplish that? There’s no easy or obvious answer. Those of us who value institutions and their importance should be devoting most of our energy to thinking about how to create a strategic environment in which an institutional reset becomes possible.

You can also read some of my previous pieces on institutional reform.

One logical approach here is to focus on the local and the small, where you and a relatively small group may have the ability to affect change. On a broader societal level it argues for federalism and localism to push things down to the level where engaged people at least have a fighting chance.

A period of strategic withdrawal, which precipitates a decline in the influence and reputation of the institution, followed by ultimate recapture, might be our best bet. Progressivism is an exclusively corrosive force, so if everyone with a robust worldview leaves, the decline is inevitable. The challenge will be recognising when we need to come back. A similar thing is playing out before our eyes with mainline and non-denominational churches.