The Future of Appalachia

South Appalachia is already turning around, and remote work offers new opportunities for North Appalachian communities too.

Many of you know that before changing focus to religion and men's issues, I was a consultant, researcher, and writer on state and local policy, predominantly looking at Midwestern cities. I've been working to ramp down that business, but sometimes, as they say, people make you an offer you can't refuse.

I just completed a new such research report on the future of Appalachia for the Urban Reform Institute. The focus was on the opportunities for Appalachia presented by remote work. As always, I tried to create value-added frameworks to give people a new way to think about Appalachia, and to provide practical insight that leaders can use to help move their communities forward.

Just as with my main work, I like to build up, not just tear down, to provide insights you can't get anywhere else, and to provide actionable ideas.

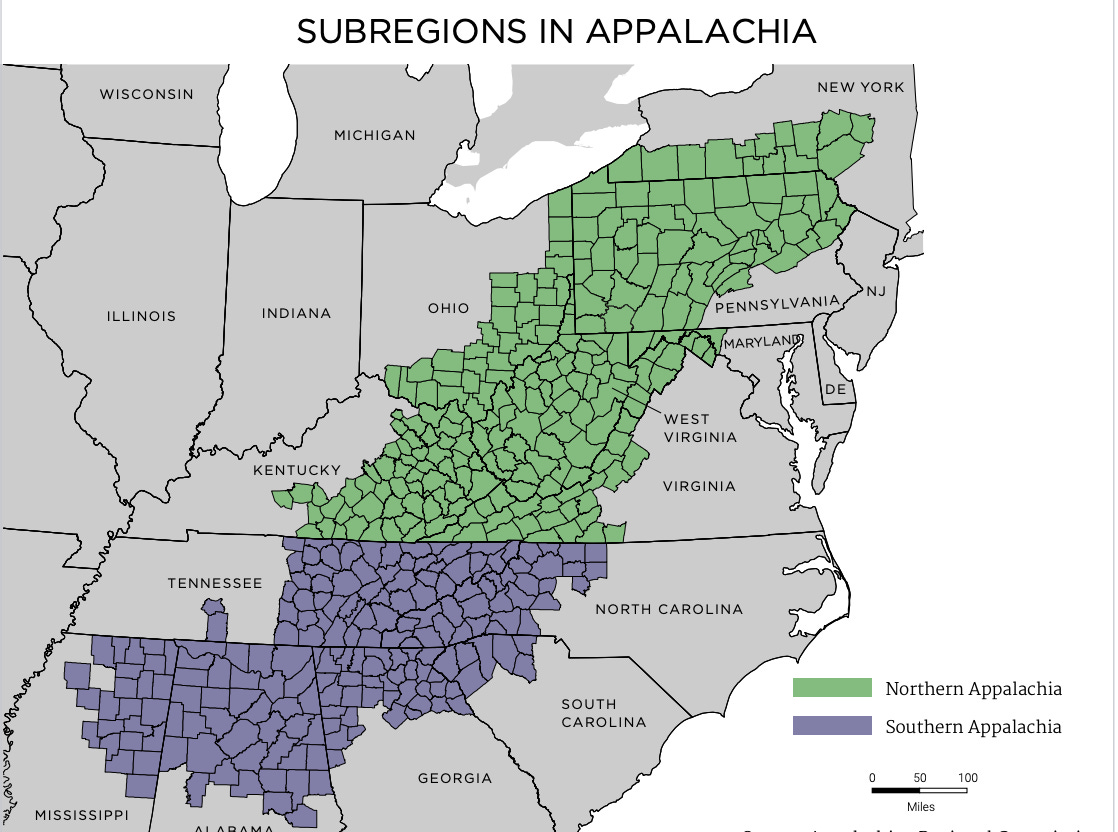

North vs. South Appalachia

Appalachia has been a byword for backwardness in America for over a century. People tend to either think about it as a single place, or to use things like the model created by the federal Appalachian Regional Commission, which has five subregions.

I instead divide Appalachia into two halves, North and South, dividing along the basic Frostbelt-Sunbelt divide. Looking at it this way, we see that South Appalachia far outperforms North Appalachia, and shows signs that it is organically redeveloping.

South Appalachia has a lower share of distressed counties, a higher share of counties growing in population (72.3%), much higher net in-migration (about 300,000 people since 2020), greater job growth, fewer drug overdose deaths, etc. I go through all the data in the report.

My north-south split is actually visible easily on this Census Bureau map of migration from earlier this year. Blue means more people moving in, orange more people moving out. You can see that the north boundary of Tennessee-North Carolina is a huge dividing line.

I don’t claim I’m the only person who’s ever thought of Appalachia this way (though I haven’t seen anyone else do it). But I do believe it’s a very useful way to analyze the region.

Also, I don’t claim that leaders in South Appalachia are somehow better than in the North. I think this is more about Frostbelt stagnation vs. Sunbelt growth, about Old North vs. New South.

Remote Work

My analysis of remote work takes up the second half of the report. Its analysis applies to anywhere - not just Appalachia. I looked at remote work across three dimensions:

Full time remote workers (newcomers)

Hybrid or part time remote workers (newcomers)

Existing local residents accessing remote work opportunities

For fully remote workers, I changed my mind about the various incentive programs that are out there like Tulsa Remote. These pay people $10,000 to move to a new city or state. I used to think this sounded desperate and was hokey. But they seem to have had some success. West Virginia’s Ascend WV program has done very well, and Eastern Kentucky’s pilot program is already showing good results. This is something communities could consider.

For hybrid work, I did a deep dive into Chillicothe, Ohio, which is about an hour from Columbus. The communities that are best positioned to profit from hybrid work are those which are a bit too far to commute five days per week, but not two days or so per week. Chillicothe falls into that category. The broader addressable market for hybrid work is suburban and exurban counties. I put together this rough map of this for the Appalachian region for metro areas of 500,000 or more people.

As you can see, the heartland of Appalachian distress in Eastern Kentucky, West Virginia, and Virginia is remote from major markets. Quite apart from remote work, that’s a challenge.

Lastly, and I think this might be the most important finding in my report, is the key role played by broker firms in connecting existing local residents to remote work jobs. For those who are already connected to the knowledge economy, perhaps they can find their own quality remote jobs. But for those who are not, it is all but impossible.

Two companies in West Virginia, CentralApp and Oktana, decided to address this talent disconnect. They identity, vet, and train Appalachian workers in market relevant Salesforce skills (including funding the training). Then they sell staffing work and put those people into those roles as remote workers.

This has produced life-changing results for some people. One CentralApp person got hired on at his client at a six figure salary. One of the people at Oktana is a former coal miner who was previously homeless for a period of time.

I think broker firms like these are critical to connecting people in many communities with real, high quality, well-paying remote work jobs.

There’s a lot more in the report, but these are the highlights. If you are interested in public policy or Appalachia in general, definitely give it a read.

Just a personal anecdote. My son-in-law wanted to move back to northern Kentucky after college here in Houston. They are both accountants and ended up south of Lexington. The Lexington and near-Cincinatti areas of Kentucky are maybe not booming but seem to be doing fine. Nevertheless, I guess the economic situation drops rapidly as you go east.

They have both worked remotely, my daughter full remote with her same Houston job. That situation has worked out very well for her. My son in law switched jobs to a Kentucky manufacturer, but even he doesn't have to go in to the plant more than a day or two per week, normally.

It seems like norms for knowledge workers are really changing. I can't help thinking that with better internet (thanks Elon & Starlink), this trend of folks moving to nicer and more affordable parts of the country will continue to have legs. I suspect state and local governments need to be focusing on how to keep the housing markets affordable, so locals can share in the rising tide.

Aaron - this is not a criticism, more of a question. I say that since I may have ultimately come to the same methodology and recommendations as you. But most of this is geared towards essentially recruiting the professional class to the region as a means toward improving its economic trajectory. Again, I understand that, agree, and think it's smart. But what do we have to say about methods to more directly improve the lot of existing residents? I know you have the one example of essentially training someone there, but what else? I fear in our world of planning/development we frequently lack ideas on how to build up the local economies of working class and rural people without "recruit smart people from elsewhere." Any thoughts on this, especially for a region like Appalachia?