Meritocracy's Blind Spot: How America Overlooks Its Own Talent

From National Merit Scholars to H1B visas, how America's elite institutions miss homegrown talent while chasing foreign labor

Tom Owens posted another provocative essay on his Substack. He doesn’t post often, but when he does it is usually thought provoking. He doesn’t shy away from potentially controversial analysis. You should definitely check out his page and subscribe. He graciously gave me permission to repost his piece here - Aaron.

The recent debate about H1B visas ignited a firestorm as tech magnates, notably Elon and Vivek, and their immigrant workers denigrated the talents and capabilities of native-born Americans. Economically, are these “skilled” immigrants predominantly a way to lower wages or a critical source of talent for American competitiveness? Is American talent effectively “tapped out” or do we do a poor job of cultivating it?

Aaron Renn, in his former life as a consultant who was involved in corporate cost-cutting efforts, who was “in the room when it happened,” firmly believes the latter, having observed the motives and actions of the organizations in utilizing these visa programs. They are designed to repress wages for entry and mid-level worker bee positions, not a scalable source of elite talent.

My personal experience agrees with Aaron’s observations. I have found in my businesses that it is not difficult to find 99th percentile talent (as objectively measured on reasoning tests) among non-elites in the heartland, as our economy is massively inefficient at identifying and developing talent. With the death in the early 1970s of IQ testing for entry-level employment due to disparate impact concerns, white-collar employers were forced to launder their need for objective talent identification through higher education.

Universities are allowed to discriminate based on heavily g-loaded college entrance exams and proudly display their average score ranges as an indication of their students’ abilities. The university a person attends becomes a marker of their perceived ability. While this doesn’t seem to affect average earnings much — the top-scoring students tend to earn about the same regardless of where they attend university — many of the most elite institutions provide a pedigree for the top, most elite jobs of our society. Eight out of nine members of the Supreme Court, for example, attended Harvard or Yale, and Barrett attended Notre Dame. None attended a state school. It is still true that for truly elite positions, pedigree matters.

More importantly, these schools have some of the best faculty, and small class sizes dedicated to cultivating talent. Since they admit some mixture of new, raw talent and established elites, the networking between the two helps raw talent develop social connections to elite networks, something unlikely to happen at most large state universities.

To what degree, then, are these top colleges objectively identifying and cultivating talent?

Using National Merit As a Proxy for Talent Repression

It occurred to me that an objective way to assess this is the National Merit program, which publishes extensive data on the students who qualify and their college destinations. It helps that the program is better for identifying talent than SAT or ACT scores for several reasons:

The National Merit Scholar Qualifying Test (NMSQT), somewhat of a misnomer, is a modification of the scores achieved by high school juniors on the PSAT calculated by doubling the verbal component relative to the math. The top 1% or so of scorers in each state are awarded semifinalist status, and 95% of these advance to finalist when confirmed by an SAT score within 100 points or so of the equivalent PSAT score. Some squawk about the emphasis on verbal scores, but the academic literature is pretty solid that verbal ability better predicts success outcomes than math ability, though both are important.

Since the PSAT is administered once1, on a uniform test date, it is a more accurate assessment of ability for large populations2, as students cannot take it more than once, and since administered by schools directly, is less prone to cheating by corrupt proctors or stand-in test-takers using fake IDs. If you don’t think this happens, you’re very naive3. The whole country of Korea had their SAT scores cancelled, and again, that’s only when the cheating was widespread enough to be obvious.

In general, the PSAT is administered before most students engage in significant test prep, and is more like the old SAT in using tricky questions on Algebra I level math to assess ability more than achievement.

At the population level, standardized test scores are the best indicators of academic ability and job performance, far superior to less objective techniques such as interviews, high school GPAs, or extracurricular activities.

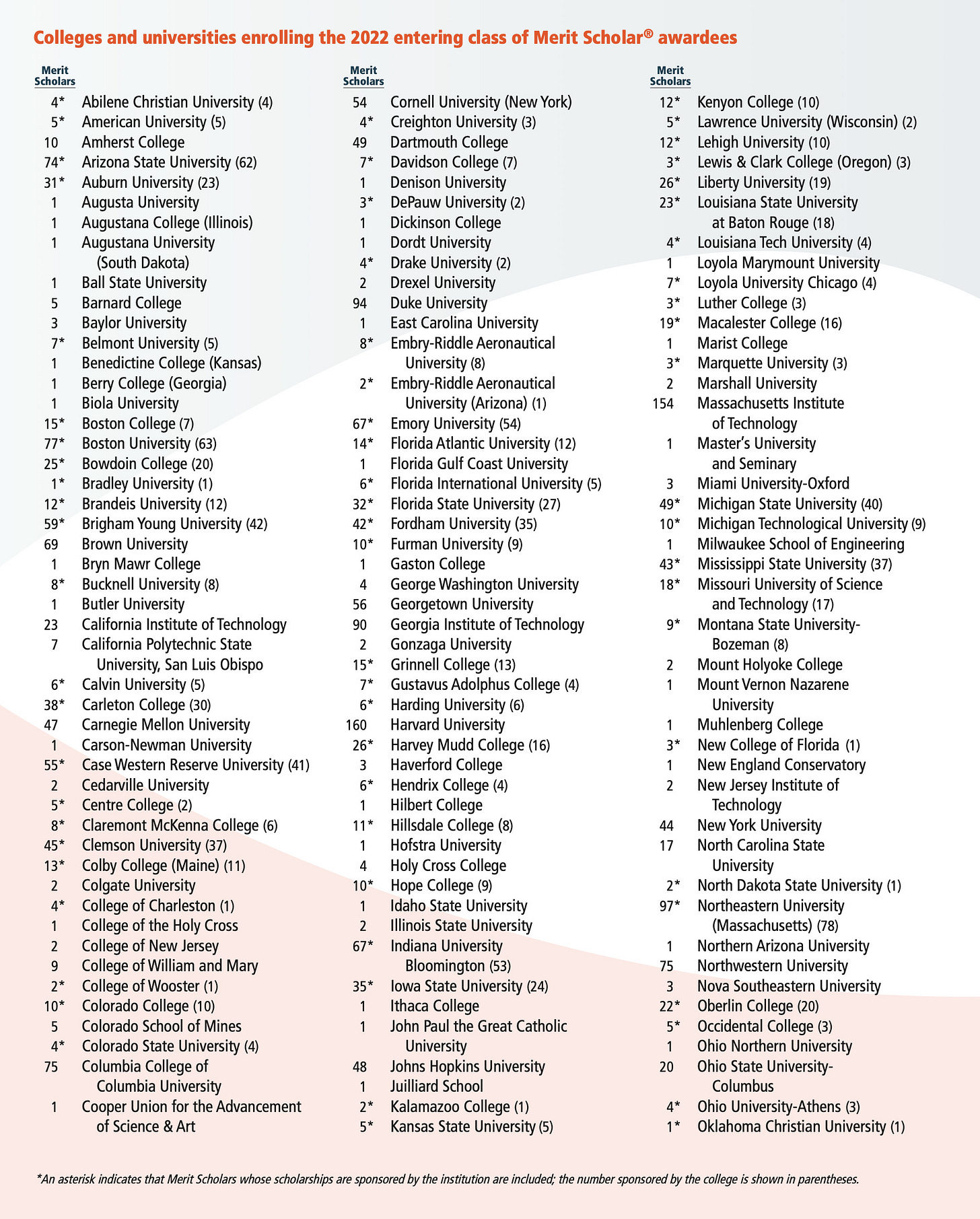

So where do National Merit Scholars matriculate? The most recent report from National Merit shows us:

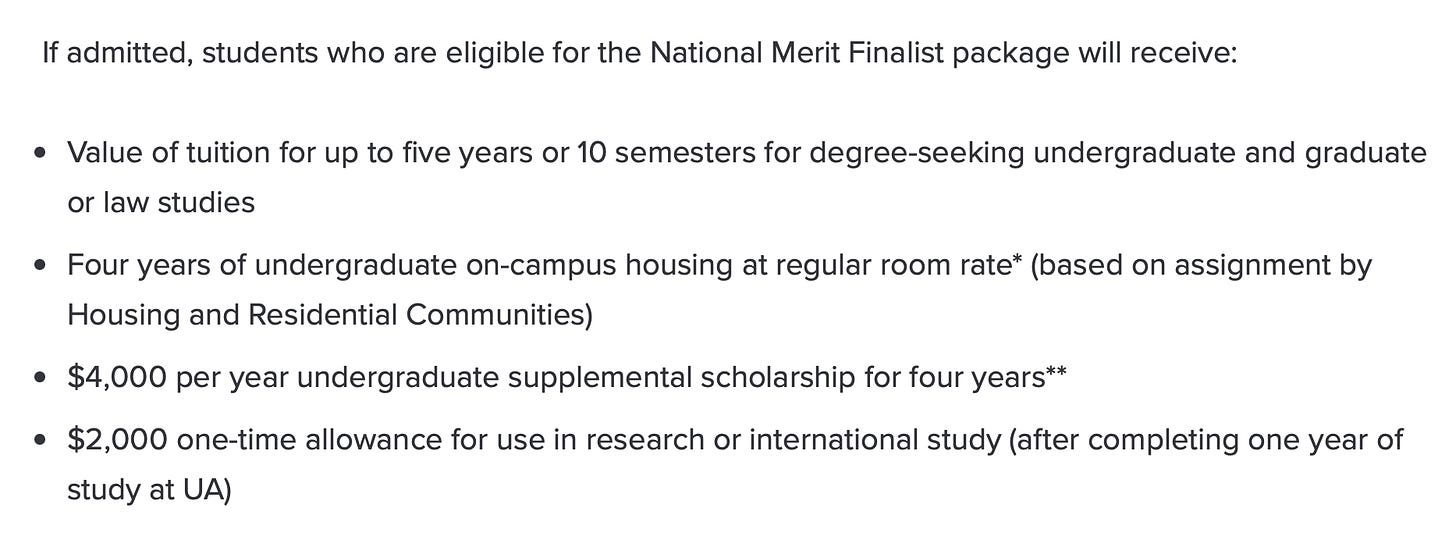

Overwhelmingly, National Merit Scholars matriculate to large state schools where they are awarded generous scholarships4. The #1 destination is the University of Alabama, which provides the following benefits to finalists:

That’s not only a full ride, but free housing, an extra $4,000 per year, and also a 5th year that will allow many students to complete a master’s degree. That last one is extremely strategic on Alabama’s part, also building up the competitiveness of their graduate programs by keeping these students in the state and their programs.

Bama is a smart operator here, applying the same principles to academic recruiting as they do to their football program. Also notable is their matching of pageant scholarships. One wonders exactly what they’re up to in just straightforwardly recruiting a smart, good-looking student body. This is a cunning long-term investment in their alumni base, as both brains and beauty are predictive of life success. Not to mention that the median white-collar professional can live like a king in Huntsville or the nice suburbs of Birmingham compared to a hovel in NYC or SF, even if it means giving up any hope of being elite.

With the growing Kardashian-grade social cachet of “Bama Rush,” — nothing seems to attract the attention of young women like a cutthroat social competition, and the boys like a good football team for similar reasons — Alabama, and SEC schools in general, are starting to see massive matriculation from the Northeast. They’re becoming a haven for smart, athletic kids from wealthy families who want to opt out of the Ivy admissions rat race, which is increasingly the province of Paris Gellar types willing to jump through the hoops setting up fake nonprofits, fake extracurriculars, and crafting social justice narratives in their essays, or else academic grinds that Vivek seems to think are the true elite (more on that later). Long-term, if the Ivies tolerate this, they will lose their cachet. It’s social proximity to smart jocks like the Winklevosses, not one-dimensional grinds, that makes the Ivies desirable.

In the meantime, however, it is a disservice to these talented students that they are either a) rejected from the Ivies and equivalent schools for DEI reasons, or b) aren’t offered comparable scholarships, particularly guaranteed scholarships that remove the risk of applying. Many of these students from lower middle-class families won’t even bother applying because of the perceived cost, as even if tuition is heavily discounted or waived the cost of housing alone often exceeds the cost of state universities. For many students, this means unnecessary debt.

Elite Universities As Social Insurance Programs

One way to see elite private universities, particularly second-tier ones, is as a form of social insurance. Because direct testing of employment applicants is legally questionable and frankly distasteful to most business leaders5, many people who graduate from these universities have a form of blindness in sourcing talent. They are prejudiced against smart graduates of large public universities, limiting themselves to hiring only from the small, inbred network of elite ones. Ben Horowitz, in The Hard Thing About Hard Things, tells of his almost not hiring an extremely talented sales executive because, despite his massive success at other companies, the candidate had attended the University of Southern Utah for undergrad.

One problem is that the people who graduate from elite universities aren’t as elite as advertised. These institutions recruit a mix of students, some highly talented, some for DEI reasons, some who curate applications that overstate their actual talent, and others who are well-connected to alumni or donors. Even Harvard has a famous “number” — i.e. the donation, in the millions, where one’s mediocre kid can get admitted. Well aware of their perceived bottleneck on talent, Ivies and others trade their cachet to camouflage the middling kids of the elite among their most talented students. And if graduates of Ivies aren’t all that talented, on average, it can look like, if one believes they are the sole source of world-class talent, that there is a general shortage of talent6.

This blindness can make people from elite backgrounds underestimate the available talent, and of course, it’s a convenient blindness if this is a cover for hiring H1B immigrants at cut-rate wages. That these workers are essentially indentured servants and cannot look for other jobs is even more attractive to employers. To use Trump’s language, if they quit they have to “go back” to where they came from. They can be abused, overworked, and underpaid with no recourse.

This is a huge benefit to employers, as a major cost in any business is turnover, particularly in California, where non-compete and non-solicitation agreements are statutorily unenforceable for American citizens free to seek another job. Because they are cheaper, they also allow corporate bureaucrats to more easily inflate headcount to justify their own promotions, a principal-agent problem I covered in my review of BS Jobs, and these workers, as a serf class, are less likely to compete with them for these same promotions.

The ability to have employees who cannot quit, essentially a one-way employment contract where the employer can still fire at will, is a huge business advantage. This advantage may even make these employees more desirable despite their middling talent levels compared to native labor. A trained, middling-ability employee who can’t leave is, in some roles requiring more training than aptitude, more desirable than a super-talented employee who can, or who will demand promotions instead of being content in a line worker role. Whether this is desirable in the American economy generally is a political question, but not publicly defensible, which is likely why we get all this hand-waving about a “talent shortage.” Following the money, the reality is employers who don’t want to lose their cut-rate serfs.

Part of it may simply be a cash-flow problem.

The New Entrepreneurs

The recent Twitter blowup on H1B with Vivek and Elon also lacks economic context. As I explained in my post last year on Elon, he is a great man playing the game as it is presented to him. The “game” in this case is the greatest Bubble of all time, and perhaps a permanent bubble, as I further explained in my post on the glut of capital.

Part of this game is that neither Vivek or Elon are entrepreneurs in the same sense that Henry Ford was. Neither have ever returned a dime of dividends to investors7, and run or ran businesses with poor financials when evaluated on a cash basis. Vivek mostly never even served real customers, given he cashed out of a failing biotech company before the failed patent he purchased with investors’ money failed a fifth time in clinical trials8.

Elon creates real products, but the glut of capital, and the laws of physics in disfavoring a less dense source of energy for locomotion9, make that difficult to do profitably. Take, for example, Tesla’s most recent annual cash flow statement, as opposed to GAAP “earnings.” Tesla spent $2.4 billion cash more than it made from operations, and to cover the gap took on debt and issued new stock, diluting shareholders. It is a cash-poor business.

Businesses like this need cheap labor to avoid running out of cash and would fail if they could not hold down wages for technical labor through H1B (and wages at the entry level tend to depress wages up the scale as well). Elon probably doesn’t see a way to pay his engineers $150k a year starting salaries in the high-cost metros where he does business, and his best engineers multiples of that, without running out of cash.

Now, it’s important to note here that startups or low-margin growth businesses have another way to pay employees when short on cash: stock options and equity grants, which also incentivize sticking around with a vesting schedule. However, since H1B serfs can’t leave and have their immigration status tied to the company, there’s less of a need for this kind of compensation, which is extremely attractive to tech founders by avoiding the “D word” — dilution. The conflict of interest here is obvious since the entire source of these founders’ wealth is usually tied up in their company’s stock value.

It’s important to note that most entrepreneurs must bootstrap and run businesses for a cash profit. Only a tiny sliver of the most privileged closest to the money printers, e.g., the Harvard and Stanford networks, can tap into venture capital willing to lose money in hopes of flipping an IPO on public investors, so it’s extremely rich for this most privileged caste — pun intended — to then demand serf labor on top of their superior access to undisciplined capital. On a cash basis, your local dentist who owns his practice is a more successful entrepreneur than most of these people.

So take their arguments about H1B being essential to American greatness with appropriate skepticism for the self-interest involved. Absent bubble economics, massive money printing, and depressed wages, we’d have different entrepreneurs solving better problems as indicated by the production of cash profits more proportional to market capitalization, and those businesses could afford to pay native employees market compensation.

Another angle on this is how so many tech founders have piled on with Elon’s call for more immigration. Elon, of course, is one of the few tech guys working on real-world problems. Most of these guys run businesses that provide marginal social value.

One tech CEO who chimed in (with a misleading comment comparing engineer wages in high-cost-of-living metros to the American median) was Aaron Levie of Box. Box is a file storage platform, basically Dropbox or Google, with more APIs bolted on to provide compatibility with corporate bloatware. No one would miss Box or half its competitors if they didn’t exist. They provide literally the most commoditized tech service imaginable, storing and downloading files, and as one can imagine in a commodity business, the profit margins are thin.

Yet tech guys like Levie glom onto Elon, who does hard things in the real world, to ensure cut-rate labor keeps their barely profitable apps running. Box, for example, has never paid a dividend and has over a billion dollars in cumulative negative earnings since its IPO. Not everyone has to run a world-changing business, and providing file storage is a useful service, but it’s not worth violating the social contract with native American workers to keep their lights on.

It might even be a blessing in disguise for society that these firms don’t recruit more heartland talent. At the margin, more of our smartest people should be working for Koch Industries in Wichita or drilling for oil in Midland, adding to our standard of living, and in metros where family formation is affordable, rather than coding another Silicon Valley me-too app for one of these cash-burning “entrepreneurs.”

Developing America’s Native Talent

Self-interested “talent shortage” rhetoric aside, what would a national talent development initiative look like? Some argue admissions should be based solely on test scores, the only objective measure of merit among students from different high schools and backgrounds, especially given the massive grade inflation of the past 30 years.

I’m not as convinced of this due to the runaway, increasing gap between the averages of Asian students and everyone else on SAT scores over the last two decades. Obviously, academic aptitude has not changed this quickly. Many attribute this to extreme test prep culture, which became more effective as the SAT was revised to become less “discriminatory” and thus more preppable.

Vivek, weighing in on the recent controversy, agrees that the issue is not so much IQ but rather work ethic and achievement:

The reason top tech companies often hire foreign-born & first-generation engineers over “native” Americans isn’t because of an innate American IQ deficit (a lazy & wrong explanation). A key part of it comes down to the c-word: culture.

…

A culture that celebrates the prom queen over the math olympiad champ, or the jock over the valedictorian, will not produce the best engineers.

Vivek here invokes stereotypes, which aren’t necessarily inaccurate but rather represent statistical tendencies with many individual exceptions. Some native American students are boring grinders, and some immigrant students engage in traditional, well-rounded American leisure activities. Since not everyone who reads this column is a “very stable genius,” making that disclaimer is important. But to answer Vivek’s criticisms I must respond by citing stereotypes, so here goes. No offense is intended to those who fall under exceptions.

First of all, Vivek’s argument, to the extent he is talking up his own cultural background, is inherently fallacious. India is well behind the United States in Nobel prizes (even excluding immigrant winners) and Olympic medals per capita and still struggles developmentally, requiring US travelers to take malaria prophylactics before visiting certain regions.

Richard Hanania, who piled on the pro-immigration side of this debate, loves to mock West Virginia, but in that state, there are no documented deaths from dysentery (infectious diarrhea), because America’s so-called “low human capital,” to use Hanania’s term, has mastered century-old sanitation technology in even our smallest, poorest municipalities. Whereas in India, preventable diseases like this kill over 100,000 children annually. Indian immigrants to the USA represent a tiny sliver of the most talented among a billion-plus population.

Further, it’s doubly misleading in comparing an elite subculture to American culture as a whole. It’s not pot-smoking high school dropouts who these immigrants are competing with, but rather the best and brightest graduates of our domestic engineering schools. As Charles Murray has documented, the decline in American social outcomes (as measured by drug use, sexual incontinence, etc) is almost entirely among the working and lower middle classes. These are serious problems that need addressing but are not germane to Vivek’s criticism. If anything, the native middle and upper classes are working harder than ever due to the declining need for generalists in middle management and competition from skilled immigration, an economic game of musical chairs as parents fret about their children’s ability to avoid downward social mobility.

Second, Vivek is peddling a false dichotomy between nerds and jocks. While the kids pursuing obscure trivia competitions like math olympiads and spelling bees will tend to be one-dimensional nerds, the social science literature is clear that athletics participation is associated with academic achievement and intelligence, as Geoffrey Miller pointed out. Further, being socially competent, and not solely skilled in academics, is predictive of lifetime earnings, as one study demonstrated that participating in college fraternities (and presumably similar social orgs) enhances lifetime earnings despite lowering grade point averages.

There’s more to life than grinding out math problems at Kumon after school. Western culture has always valued a balance among mental, social, and physical pursuits, and it turns out that it pays to do so! Maybe Vivek should be more a student of American culture than a critic given America’s and the broader West’s historic accomplishments.

Nevertheless, Vivek’s point stands generally for the individuals in question, in that there are immigrant subcultures that certainly work harder on high school academics than even the norm for the brightest American students. This leads to a philosophical question about achievement vs. aptitude. Is it better to source high achievement externally (directly, or indirectly, via the children of high-effort immigrants) or search internally for high aptitude?

Consider two students, both of whom have 1500 SAT scores. Student A comes from a grind culture where test prep is a family tradition starting at 10 years old, accompanied by hours of after-school tutoring. Student B is a football player from a rural high school with precociously good grades who “gets” math and verbal concepts despite deficient instruction at his high school, and who took one practice test before walking into his SAT on a Saturday morning after the Friday Night Lights.

Which student would most benefit from an elite education? Clearly, Student B, whose score reflects higher aptitude, i.e., higher achievement with less effort. In fact, this was the original purpose of the SAT, to identify high-aptitude students who did not attend elite Northeast prep schools. In some sense, students who overly prep for the SAT are showing fake aptitude relative to their scores.

That used to not be a problem because the old SAT was notoriously difficult to show any efficacy of test prep. It required only basic reading and math skills at the Algebra I level and derived its difficulty not from advanced procedural algorithms, which can be taught, but rather from requiring students to demonstrate a deep understanding of verbal and quantitative nuance. Getting this right in admissions testing is a subtle science.

Measuring aptitude is quite easy when stakes are low and one only wants population-level estimates. For example, a simple ten-item vocabulary quiz called Wordsum is sufficient to estimate IQ for large groups in national surveys, when participants aren’t incentivized to study beforehand.

But high-stakes testing for individuals is an extreme application of Goodhart’s law: any useful measure loses its utility once it becomes a target for those being measured to hack. Almost all human knowledge is g-loaded absent incentives, but most of it is g-hackable. And the new SAT works perfectly well for students who do not overly prep, but fails when their scores are compared to those who do.

Strangely, of all test items, vocabulary is most g-loaded for native speakers of a given language, particularly English given its gigantic inventory. This may seem counterintuitive, for surely “disadvantaged” students would lack vocabulary due to fewer opportunities, or less verbally adept parents. However, this fails to account for the role that intelligent students play in fostering their own environment.

A rather famous example is that of Oprah Winfrey, who, despite growing up in Jim Crow Mississippi, managed to read most of the books in her tiny local library. High-aptitude individuals like Oprah, even in relatively deprived environments, usually manage to get their hands on reading material, which their curious minds crave for sufficient stimulation, given their voracious appetite for knowledge, and their brains vacuum up information easily and store it away efficiently, building vocabulary. Today, these theoretical disadvantages are even smaller with unlimited free reading material available online.

The hated analogies and antonyms of the old SAT were generally test-prep-proof types of questions. Given 50,000 English words, the addressable analogies and antonym space numbers in the billions, a number of relationships impossible to study in advance, beyond reading widely for pleasure and understanding the basics of how analogies and antonyms work. Similarly, the old quantitative comparison items on the math section allowed the testing of a deep understanding of basic math concepts rather than students’ more preppable computational abilities.

Getting rid of these older items in the name of disadvantaged groups has ironically attached a higher yield to the test prep efforts of the most advantaged and grinding students. And some students have to work in high school, or choose to play sports, and simply can’t or won’t grind for hours after school on narrow academics.

Perhaps the modern test most similar to the old SAT is the LSAT for law school admissions. Unlike the GRE or SAT, it retains a full-range difficulty level where almost no students achieve a perfect score, and it tests purely for logical and verbal aptitude, not legal knowledge. Unlike the new SAT, where extreme test prep has led to runaway gaps between students from grinding cultures and everyone else, the LSAT shows performance (p. 24) between groups consistent with the broader academic literature of low-stakes aptitude testing, i.e., excessive prepping does not help performance.

This difference is subtle but important. Eminence in one’s field requires more of an ability to respond to novel situations than overstudying existing knowledge, and high-aptitude students can catch up on high-school-level achievement in a semester or two of freshman classes. Especially if DEI is now illegal, it is extremely important that our meritocracy reflects the right kind of merit, expending scarce elite educational resources on well-rounded students with aptitude rather than those simply willing to grind. At least, that seems more like the American way than the opposite. We want to reward and develop talent that delivers results in novel situations, not simply rewarding linear functions of effort.

It’s clear elite universities want to admit well-rounded students with an inherent desire to learn instead of outcome-focused students who care more about what’s on the test, and the best way to achieve this objectively and without accusations of bias is to pressure the College Board to reform the SAT back to its old aptitude-based format. Children of certain immigrant cultures will still likely outperform native Americans due to simple selection effects, but it won’t be a runaway gap due to extreme test prep efforts, and elite universities can maintain their cachet with fewer Winklevosses heading to Tuscaloosa for a four-year bacchanal.

Further, schools ought to value participation in high school athletics more highly for admissions and scholarships. Team sports in particular teach people skills and frustration tolerance on a physical level and produce a balance between brains and brawn that enhances practical cognition rather than book learning.

Students with athletic backgrounds have higher lifetime achievements and are more likely to be the most successful, generous, and loyal alumni. A particularly creative scholarship might feature a weighting of something like 1/3 grades, 1/3 standardized test scores, and 1/3 the students’ performance on a modified NFL combine relative to a minimum qualified floor in each category. If some students over-prep for the latter by becoming extremely physically fit, so much the better!

Eliminate Disparate Impact

Perhaps the most powerful change, which could be achieved with some combination of executive, legislative, or judicial action, would be the elimination of the disparate impact “back door” of proving discrimination against protected classes. If we wish to punish discrimination — and there’s an argument, advanced by Rush Limbaugh and others, that irrational discrimination is self-punishing enough in the marketplace in that businesses deliberately choosing suboptimal employees for non-economic reasons will suffer competitively — then we must at least return to the common law standard of mens rea before interfering in the job market. That is, only conscious, intentional discrimination should be subject to federal sanctions, consistent with the letter and spirit of the Civil Rights Act.

Disparate impact is the source of companies’ anxiety about the racial makeup of their workforces despite equal-opportunity hiring practices. This relates indirectly to the H1B issue. While Indian or East Asian immigrants do not advance goals of increasing the “underrepresented,” they have the virtue, under the DEI regime, of being not white males. When reporting totals as required under federal law for larger employers, these employees at least don’t count against them, whereas, in how the law is applied, every white male hired represents potential evidence for a discrimination claim.

Freed from the need to outsource cognitive testing through university pedigrees or worrying about disgusting nose-counting of employee demographic characteristics, businesses would be free to develop their own independent standards and internal training programs and more widely source employees without worrying about the ethnic background of potential talent. There’s no obvious reason why many jobs should require a college degree and could not be taught on the job in apprenticeship-like models. Young people could start families sooner without wasting four years of their adult life and the burden of student debt.

Let the market figure it out. There’s a huge incentive to undercut the profligate university-industrial complex.

Cover image: Vivek Ramaswamy by Gage Skidmore, CC BY-SA 2.0

Since the SAT and ACT allow unlimited retakes, students can opt to report only their highest score, and the retake standard deviation is 50-60 points, a student who takes the SAT five times would expect to report a score 60-70 points higher than a student who takes it once. This raises a 75th percentile score to the 86th percentile.

Smart college admissions departments would be wise to offer automatic admission based on PSAT scores. Students really do hate taking the SAT and ACT, and all of the other crappy college admissions songs and dances necessary under unreliable “holistic” admissions policies. Guaranteed admission based on a single test date, and ignoring garbage resume padding, would be highly desirable to students, relieving their anxiety about the admissions game and letting them enjoy their youth instead of curating their lives for an admissions application.

Stanley Kaplan, the pioneer of the test prep industry, started by holding pizza parties for post-SAT test takers, at which his staff would quiz them and write down remembered test questions. Senate Minority Leader Chuck Schumer was an early employee who ran the copy machines for Kaplan, so he had advance access to likely questions and eventually scored 1600.

An important caveat here is that this report only covers National Merit Scholars, not National Merit Finalists, and there are state-level differences in the qualifying scores, but again by taking the top of each state National Merit corrects for unequal educational quality and test prep culture among the states, better identifying hidden aptitude in flyover country. Scholars are finalists who receive a National Merit scholarship through National Merit itself, a university they attend, or another organization, such as their parent’s employer. Only about half of finalists receive these scholarships (as National Merit cannot fund 100% of them), and many elite colleges do not offer National Merit scholarships. So, an argument could be made that the overall distribution of finalists — who are academically equal to scholars — would be less tilted towards large state universities. Still, however, since half of the finalists do receive scholarships, and the distribution is so overwhelmingly tilted towards non-elite schools, it makes my point indirectly. If students who need money to attend school are avoiding elite universities because of costs, when these schools have endowments that could easily cover full scholarships, that would seem to indicate that elite universities are doing an extremely poor job cultivating native American talent. If the Ivies were more serious about sourcing 99th-percentile talent over providing social insurance to the 90th-percentile children of elites, they might even be successful in getting students to read a book.

I find that it is true, per The Millionaire Next Door, that the C students in undergrad tend to hire the A students. This is because high intelligence with its usual correlate of high conscientiousness makes people extremely cautious; entrepreneurship, in contrast, requires a willingness to take on some but not too much risk, and thus a rarer, unstable combination of usually inversely correlated traits: high openness, moderate to high intelligence, low to moderate conscientiousness, low to moderate agreeableness, and moderate but not quite criminal levels of narcissism / Machiavellianism. As someone who made my fair share of Cs as an undergrad, I love hiring people smarter and more conscientious than me who will do a better job operationally than I ever could. Many business owners, however, remain sore about their own academic history and, if blinded by too much narcissism, will refuse to accept the science regarding general reasoning aptitude and job performance, not realizing that the skills and capabilities one needs in workers are different and complementary to those of the entrepreneur. Instead of hiring the smartest, most conscientious people to clean up the entrepreneur’s mess of a “minimum viable product,” they trust their gut and hire people more like themselves, which creates more mess. There’s only room for a few foxes in most henhouses.

As I noted in my review of BS Jobs, “Koch Industries, one of the largest private employers, prefers hiring smart kids from regional state universities to get hungry, motivated workers. Charles Koch has shared how other executives at public companies don’t believe him when he says the smartest graduates of Wichita State outperform Ivy Leaguers due to their lack of entitlement.”

The only way businesses provide real returns to investors, i.e. generate net financial benefits to investors other than capital gains — which when realized are simply funds, like a pyramid scheme, that come from other investors — is through dividends and stock buybacks. Neither Tesla nor Vivek’s private equity concern has ever done this.

Strangely, the 5th clinical trial was conducted by Vivek’s, I kid you not, literal mother, which would seem to be a huge conflict of interest. The Vivek business model was to buy failed drugs and then get first-degree relatives to run a new clinical trial, umm, expecting different results?! It must have been quite the dud of a molecule if this arrangement couldn’t p-hack what they needed.

The Cybertruck, for example, has a 123 kWh battery that weighs 1,600 pounds, or 0.09 kWh per pound when adjusted upwards 20% for the captured energy of regenerative braking. My diesel truck holds 24 gallons of fuel, or 168 pounds, which when adjusted for its mechanical efficiency of ~40% is 365 kWh, or 2.2 kWh per pound. A conventional diesel truck enjoys an effective fuel energy density about 24 times higher than the Cybertruck.

So much to digest but great piece. A few random thoughts on items discussed:

Ivy Leagues - the only time I worked with Ivy Leaguers was on Capitol Hill early in my career. Generally they were entitled, not particularly hard working, and there were plenty of people from non-elite schools that were just as smart. I would rather have a team of Big Ten grads working for me than from Harvard.

Sports - I am a big believer in the value of sports for developing mental resilience and teamwork, and like the idea of colleges taking participation into account, but with the emphasis on participation rather than too much on achievement. As a parent of HS and MS aged kids, the sports arms race these days is absurd compared to when I was their age to be competitive for a varsity slot for basketball, baseball, volleyball, soccer, etc.

Disparate impact - needs to be struck down by SCOTUS, as it's an awful doctrine that handicaps the effectiveness of our workforce in many critical areas. This is going to be tough because along with the assault on DEI, it's going to primarily affect blacks and reduce the number of stable middle class jobs they can get. This is definitely a hill the left is willing to fight and die on, and I think Barrett and Roberts instincts will be to split the baby on this, which is effectively letting it continue.

I'm glad this provided a more robust response to Vivek than my own, which was basically, "If what you're saying is true, why isn't India known for cutting edge technology rather than poop in the streets?"