The Maturation of New Calvinism

From evangelical influencers to sustainable subculture: How the Young, Restless, and Reformed movement evolved over two decades

The New Calvinism, or “Young, Restless, and Reformed” movement was one of the hottest things in evangelicalism for about a decade after Collin Hansen’s 2006 Christianity Today article that put a label on the movement.

Now, almost 20 years on, the movement has changed considerably. New Calvinism has shifted from an “All-Star team” model designed to exert influence over the broader evangelical world to a post-superstar model that primarily serves its own community. This represents the maturity of the movement, perhaps putting it on a sustainable footing for the future.

The best treatment of New Calvinism is sociologist Brad Vermurlen’s book Reformed Resurgence: The New Calvinist Movement and the Battle Over American Evangelicalism. This book is an adaptation of his doctoral dissertation at Notre Dame. I hosted Vermurlen on my podcast three years ago to discuss this important work:

Vermurlen uses a framework called “strategic action field theory” to model New Calvinism as one faction among several vying for dominance over the evangelical field. A “field” in this case is a complex entity that contains elements of a field of practice and a playing field or battlefield. He writes:

Evangelicalism in America writ large can no longer properly be considered a unified Christian movement but instead is a heterogeneous arena of conflict and contestation—that is, a field. It is not merely diverse; it is divided.

And:

The crucial insight from strategic action field theory that helps to explain the New Calvinism is that through social processes of game-like contestation, leaders of movements and organizations strategically battle and vie with their competitors for a more advantageous position in and over their field, which is defined by possession of symbolic capital and power.

He identifies several different groups within evangelicalism, including mainstream evangelicals, progressive Emergents, and neo-Anabaptists. The New Calvinists were far from the largest group numerically, but generated influence out of proportion to their numbers. They were even in a sense in a dominant position over the field.

Despite only being one “corner” of American Evangelicalism, the New Calvinism’s celebrity star-power, publishing and media prowess, and (especially) its conservative positioning in relation to the mainstream of its field put it decisively in a dominant and incumbent position.

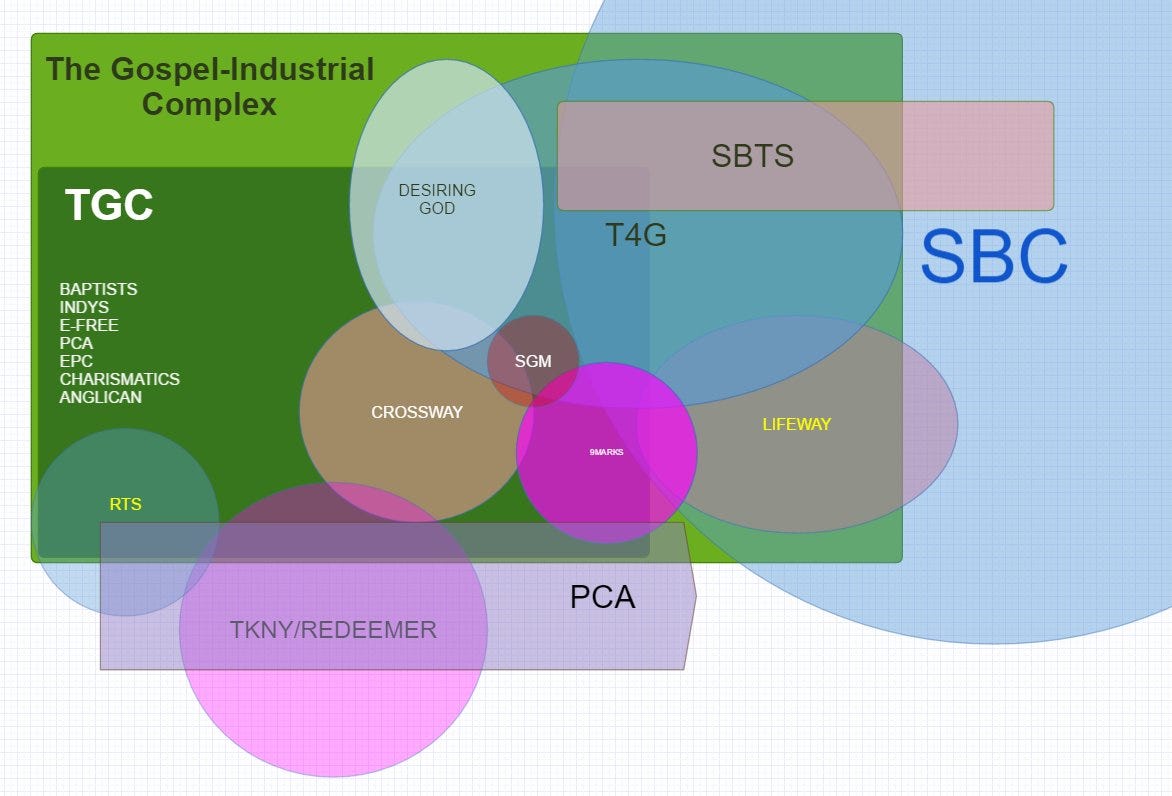

We see this dominance in the fact that the people sometimes referred to as “Big Eva” are disproportionately from the New Calvinist movement. Brad Isbell, a confessionalist Presbyterian podcaster who is often skeptical of the New Calvinism movement, calls it the “gospel-industrial complex,” and created this chart of the major parts of the movement. (TKNY is Tim Keller).

Vermurlen highlights some of the ways that New Calvinism operated as a power projection network (my term):

It begins by showing multiple ways New Calvinist leaders strategically positioned themselves in relation to their field competitors to secure a “competitive advantage” (especially among university-educated young people) over other expressions of Evangelical Christianity. These include providing clear “black and white” answers; promoting traditional notions of masculinity and femininity [in reality: pseudo-traditional - AMR]; offering historical rootedness within a tradition of the Church; deemphasizing autonomous will and self-direction; evincing theological seriousness; focusing on elite urban culture; and being apolitical and nonpartisan…As part of this positioning, many New Calvinist leaders have also positioned themselves as the gatekeepers of the field’s established orthodoxy, trying to enforce who is “in” and who is “out” based on the “rules of the game.”

The power of New Calvinism came from three key factors in my view: its social momentum, its superstar leaders, and its media mastery.

In terms of social momentum, Vermurlen uses “acceleration” as a symbolic term for this:

The suggestion is that the New Calvinism’s “force” is best explained not by measuring out its mass (i.e., the number of persons and organizations involved in it) but instead by its acceleration—its change in “velocity,” so to speak, over the last twenty years. By “acceleration” and “velocity” here, I do not mean anything overly technical; I am using them heuristically to indicate a complex of other, more symbolic factors besides “the hard numbers” (mass) that has propelled the New Calvinism as a “social object” through its field.

Like the Macarena, New Calvinism benefitted from getting hot. It was, for a time, the “current thing.” We see this perhaps most significantly in a 2009 Time article that listed New Calvinism as one of ten ideas changing the world. But nothing stays hot forever. Vermurlen notes that the peak energy of the movement passed by 2014.

New Calvinism was also characterized by its superstar leaders such as John Piper, Tim Keller, and Mark Driscoll. In part, the movement could be conceived of as an All-Star team.

When I read sociologist James Davison Hunter’s book To Change the World, I immediately recognized the New Calvinist parachurch organization The Gospel Coalition as an attempt to operationalize Hunter’s observations that culture changes from the top down via elite networks at or near the cultural center. TGC was the institutionalization of just such a Hunterian elite network, though one aimed not at changing the world, but exerting influence over the evangelical field itself. Given the Hunter was a close personal friend of TGC co-founder Tim Keller, I don’t think it’s a stretch to suggest Hunter’s ideas likely influenced the creation and structure of TGC.

Today, nearly two decades later, the founding superstars are all but gone from New Calvinism. They are either dead (Tim Keller), departed (John MacArthur, a peripheral figure to the movement), disgraced (James MacDonald), or retired (John Piper). Quite a number of key figures had scandals.

The net result today is that the movement is largely post-superstar. There are plenty of talented leaders with big churches. But they don’t have the reach or sway of say John Piper. His famous “seashells” sermon from 2000 influenced an entire generation of young evangelicals. Tim Keller could easily get an op-ed placed in an elite publication, or get a major columnist at one to do a sit down with him and report his perspective. There’s nobody of that stature today. And perhaps in a world where evangelicalism is, as Vermurlen put it, “losing its coherence,” and in today’s fragmented social media landscape, superstars of that level will simply be fewer and farther between in general.

In terms of media mastery, New Calvinism excelled across multiple dimensions. Their leaders cemented friendly relationships with key figures in the elite secular media. They had a major aligned book publisher, Crossway. And they were masters of the Internet. Tim Challies noted especially the role that Internet mastery played in the rise of New Calvinism.

There is one factor that neither Dever nor Taylor has listed and one I consider absolutely critical to the growth of the movement: the Internet….The New Calvinism is a distinctly twenty-first century, digital-era development. It is the Internet in general, and social media in particular, that first tied the movement together and that have since drawn people in….Thus this movement has not been carried by magazines or radio or televangelists–not primarily. Rather, it has been carried by the new media, the videos and blogs and podcasts. It has been carried by books that have been reviewed on blogs and purchased online.

Challies wrote that in 2012. The Internet today is vastly different. It has moved much more to social media like Twitter and Tik Tok. Google basically destroyed the original blogosphere by putting its thumb on the scales to prioritize major media pages and to downrank blogs. This had to have negatively affected New Calvinist web sites. Today, social media platforms limit links or actions that would cause you to leave their platforms. The net result is a vast loss of referral traffic to web sites from Facebook, Twitter, Google search, etc. You either get big as a darling of the algorithm natively on those sites, or you succeeded by building a direct connection with an audience via email newsletter (like this one). Podcasts are still big, but the form of podcasts that people preferred changed.

New Calvinism did not effectively navigate these changes in the Internet landscape, significantly curtailing their online impact in today’s online ecosystem.

It’s also worth noting that the heartland of New Calvinist followers was elder Millennials (like Collin Hansen). But Generation Z has a very different outlook on and orientation towards culture. New Calvinism is no longer “young.”

The net result of passing through the hype cycle, entering a post-superstar world, changes in the social media landscape, and generational change mean that New Calvinism’s ability to project influence over the evangelical field has radically diminished. In short, New Calvinism is no longer especially influential beyond its own adherents, especially compared to the way that it once was. People associated with the movement still attempt to project that influence, but it no longer packs the same punch.

But it would be a mistake to conclude from that that New Calvinism is dead. In fact, there still seem to be a great many people who are energetically engaged in the movement and its institutions.

For example, I went to the last Gospel Coalition conference in 2023. It had a full house, a packed exhibitor hall, and world class speakers. I’m a decent public speaker, but I probably would have been in the bottom quartile of this bunch. It wasn’t just style either. There was a lot of substance and meaty material there too. I also thought there was a lot of energy in the hall. This attested to a still vibrant movement.

What I see is a movement that’s matured beyond its original founding. It has been able to persist in the face of the loss of its superstar leaders - and quite a few scandals among them - which is no small feat. It still has a pretty good sized core market.

There is going to be group of people from select demographics - educated strivers in urban centers, college towns, and professional class suburbs - to whom New Calvinism is going to remain very resonant. New Calvinism speaks to their cultural values in ways that other evangelical subcultures do not. For example, most of these folks, even if some of them did vote for Donald Trump, are certainly not Trumpists and definitely reject the Trumpian style. They are more simpatico with urban progressive culture than the median red state MAGA culture. They are overwhelmingly college educated, and want more intellectually substantive fare.

New Calvinism more than any other subculture within evangelicalism is well positioned to serve this market. Provided they do it well, there’s no reason they can’t keep doing it successfully for a long time. This is moving beyond superstar dependency to sustainability.

What New Calvinists won’t be able to do is gatekeep or shape the overall ethos of evangelicalism. They probably also won’t be able to sustain their position as self-appointed guardians of traditional orthodoxy, particularly if they cross the Rubicon and embrace women’s ordination (or at least downgrade its significance).

It might actually be healthier if they stopped trying to play referee and simply embraced that they are a subculture. Winston Churchill is supposed to have said, “Nothing in life is so exhilarating as to be shot at without result.” But the flip side is that nothing is so discrediting as shooting without results. Successful gatekeeping credentializes. Unsuccessful gatekeeping decredentializes.

One of my themes is that in a Negative World, evangelicals need to be much more concerned with what they are doing than with what other people are doing. I think this principle applies within evangelicalism as well. Rather than fighting over control of the field, perhaps embracing fragmentation is the best route. I believe it works with rather than against the grain of American Protestantism, and offers the possibility of solving some of the longstanding problems of evangelicalism such as the proverbial “scandal of the evangelical mind.”

But that’s the subject of a future article.

Note: The news this week was devoured by politics and so I am posting this rather than my typical weekly news digest. Hopefully this pattern does not end up persisting throughout the second Trump administration.

Cover image: John Piper by Micah Chiang, CC BY 2.0

I learned a great deal from, and will always be grateful to, Keller and some of the others here. I remember thinking during their heyday: wow, what a great team!

What most strikes me, looking back, is how a series of new political issues came up that split the group (as far as I can tell, looking in from the outside): Black Lives Matter, Trump, COVID, etc. etc. the usual laundry list.

It was a lesson to me that you can be 100 percent in doctrinal agreement and fellowship with someone, and suddenly wake up and be deeply divided by worldly political issues. Apparently this division couldn't have been prevented.

Moving out a bit from this specific group, I could never have predicted that, e.g. Christianity Today and Russell Moore would have ended up as 'woke' as they are. Or that hard-right (Stephen Wolfe) or far-far-far-far-right (Corey Mahler) figures would have the following that they do. Not sure how things are going to look in another 10 years.

Good overview Aaron. I think it's balanced and on-target.

>New Calvinism speaks to their cultural values in ways that other evangelical subcultures do not. For example, most of these folks, even if some of them did vote for Donald Trump, are certainly not Trumpists and definitely reject the Trumpian style.

A prediction I've had for a while, and it's probably a no-brainer: regardless of how well Trump delivers, most Americans are going to be very, very sick of the Trumpian style by 2028. Including many who voted for him. It will probably be a good moment to have cultivated a plainly non-Trumpian style and aesthetic.

I think back to how sick so many of us were of GWB in 2008. Including those of us that voted for him twice and voted for McCain! I think the effect will be even larger than that.