Today I’m going to examine the most well-known and important social transformation of modern history that has been most insufficiently grappled with by the church. It is actually two transformations, the first a shift from a pre-industrial to an industrial society, followed by a shift from an industrial to a post-industrial society. My description of these is mostly drawn from others but includes some original framings and observations, particularly in the transition to post-industrial.

Note that I talk about a shift in “society” here, not just economy or methods of production. I won’t oversell the economic structure as the determinate force of this. But clearly, changes in economic structure of society were tightly bound up with changes in many other aspects of the social structure.

The vast majority of civilized human history was pre-industrial. The industrial age began in the 18th century in England and got underway in force around 1830 in the US. Much of the rest of the world started transitioning later, and there are parts of the world today that still operate in a largely pre-industrial manner. The transition of the USA to an industrial society took a very long time, but was essentially complete sometime around 1950, with only some straggling rural areas remaining in the old pattern of life. Around 1965 America started transitioning to a post-industrial culture. Only a few places in America, like Manhattan where I currently live, operate according to a predominately post-industrial paradigm, but it continues to extent its reach further with each year and I believe represents another paradigm shift in society.

As I describe these changes, keep in mind that the entire Bible was written in and about societies organized on a pre-industrial basis.

From Pre-Industrial to Industrial

The signature attribute of the civilized pre-industrial economy is that it was based on household production. Think about, for example, Abraham and his large flocks. As with Abraham, the overwhelming majority of these enterprises were agricultural in nature. However, there were other enterprises including metalsmithing or various trading activities that were on a different basis. St. Joseph, for example, was a carpenter. Some of the disciples ran a fishing business. These societies – say patriarchal Canaan vs. the first century Levant – were radically different from each other. But they had in common that they were based around household production.

An example of how this worked in the US is the homestead farm. Columbia professor Ann Douglas gives us a sample of it in her book The Feminization of American Culture (alas, an inapt title as it implies a polemic but is actually a richly detailed portrait of some of the social consequences of societal industrialization, such as the rise of mass consumer culture). She focuses on the role of women.

In 1800, by any reckoning, America, North as well as South, was an agricultural nation. Only six percent of its population of five million lived in towns of 2,500 or more; only New York and Philadelphia could have over 50,000 inhabitants. The common productive unit was the rural household; the processing and preserving of food, candlemaking, soapmaking, spinning, weaving, shoemaking, quilting, rugmaking, and many other activities all took place on domestic premises. Although extra income might be sought through the sale of produce and goods, such households were more or less self-sufficient. Buying and selling, when it occurred, was often conducted on a barter basis. The system of household industry prevalent in the Northeast through the early decades of the 19th century meant that the majority of the women in the area during that time were actively engaged in the productive activities of feeding, clothing, and equipping the nation. Nowhere was their importance clearer than in the domestic manufacture of woolen goods, most notably “homespun,” a coarse all-wool and usually undyed fabric from which most of the clothing worn in the Northeast was made. The census of 1810 estimates that 24 of every 25 yards of wool produced in the United States was of domestic origin.

The shift to an industrial mode transformed the mechanism, location, and organization of production. Rather than household enterprises, production shifted to the factory, and paradigmatically to the vertically integrated corporation. This led to a transformation of household life. As the household economy was abandoned, the husband went to work as an employee of an industrial firm, while the wife lost many of her productive functions (and political rights) and became focused on child-rearing and, increasingly, consumption, creating the nascent form of what we now know as mass consumer culture. Douglas calls this the “disestablishment” of women paralleling the disestablishment of the state churches during the same time. She says that, “middle-class women in the Northeast after 1830 were far more interested in the purchase of clothing than the making of cloth.” This initially affected a minority of households, but eventually grew to encompass all of society after an extended transition period, reaching its fullest form in 1950s suburbia and the sex role division of labor it encompassed.

This transition dramatically increased productivity but came with many hidden costs. For example, the productive household was poor by our standards, but was also at least partially self-sufficient. The Colonial farm may have been at the mercy of the vagaries of the weather, but was largely a self-contained unit that traded for outside goods in a limited fashion. The industrial household, by contrast, was completely dependent on the marketplace. It produced nothing and so needed to buy everything it consumed. This meant it needed constant inflows of cash just to survive. The husband now entirely relied on the goodwill of an employer to obtain this cash and provide for his family. The sex role division of labor that rendered the rest of his household non-productive dramatically increased this dependency. (Today, researchers like Brad Wilcox still point out that married men make more money than single ones. In part this is because married men with a family to support are under much more economic pressure to produce. It was long a truism that companies preferred to hire a family man for this reason).

Beyond the economy and sex role division of labor, a vast array of other changes in household structure took place. Just as the industrial economy took away the productive function of the household, it likewise stripped away many other functions that the household previously performed.

For example, the household was often a source of community governance. We see in the Bible the elders of the city gathered at the gates, adjudicating disputes. In the American context, we can think about the New England town meeting. Industrial society, with its enormous corporations like the railroads, required a powerful centralized state organized on industrial principles to serve as a counter-balance. What’s more, industrialization went hand in hand with mass urbanization. As recently as 1910, only 10% of the world’s population was urban. Today it’s over 50% and heading toward 75% by midcentury. Take a look at what’s been happening in China in the last two decades as mass industrial development went hand in hand with radical urbanization. This gives you a picture of what happened a century ago in the US. (The US hit 50% urban around 1920). The late 19th and early 20th centuries saw the arrival of huge metropolises like New York and Chicago, along with a host of other large cities. These cities also required large scale, industrialized government. In an era of big corporations, big cities, and big governments, the small household was relatively powerless, and also totally unable to providing the substantive, meaningful governance functions it had exercised in the largely rural and village environment of pre-industrial society.

The pre-industrial household did many other things as well. It not only provided for childcare, it was also where the education (mostly vocational training) of children took place. It was the provider of health care, elder care and most other social safety net functions. In many instances the household also provided a source of what we’d consider policing and defense. A great example is in Genesis 14, when Lot is captured during a battle, Abraham mustered the men of his extensive household to go rescue them. In the Old West the citizen posse supplemented the very limited law enforcement. (The police force as we know it is was created in 1829 in London – a product of the industrial era).

During the industrial era, all of these services migrated to either the marketplace or the state. Schooling was formalized and institutionalized in public schools, and was extended to twelve years for everyone by the high school movement. We now have hospitals (very different from the medieval Catholic hospitals), nursing homes, police and fire departments, welfare programs, an army, etc. Overwhelmingly we procure formerly household produced services from these external entities. This again increases our dependency on the market and the state to provide these services.

The need for the pre-industrial household to serve so many critical functions meant that they were organized on the principle of extended families, with a patriarchal form. The household as we think of it today may have been an extended family household, but was also commonly tied to neighboring kin into clan or tribal type structures, as in ancient Israel or places like Afghanistan today. There was strength and safety in numbers.

My impression is that Europe featured less of an extended family form than other regions, possibly because of the church’s ban on cousin marriages that are often used to strengthen clan loyalty. The US, as a frontier/settler nation, was likely even less extended family oriented. But even here we can think of things such as the Hatfield-McCoy feud. The Joad family in The Grapes of Wrath, who represent the last vestiges of pre-industrial American being mercilessly crushed by the industrial age as symbolized by the tractor, is also a small extended family.

The industrial age, by contrast, featured a nuclear family structure. Urbanization that drew people away from family in the village played a big role in that. We see it playing out before our eyes today in China, where there are big problems reconciling traditional notions of filial responsibility with the reality of an urbanizing country as children move away. The industrial nuclear family retained its patriarchal structure, however.

We see the industrial paradigm in its fullest form in the 1950s suburb, with a husband commuting to an office or factory, employed by a large corporation, while the wife stayed at home. Stripped of most of its functions, the nuclear family household became a locus primarily of companionship, consumption, and childcare, possibly with some elder care or other minor items added. The family also continued its governance function in an attenuated way in the form of the civil society activities whose decline in post-industrial America is now so often bemoaned: the Kiwanis Club, the bowling leagues, the garden clubs, the labor unions, etc. These were thin communities that replaced the previous thick communities of extended family, guilds, monasteries, the feudal order, etc.

Finally, pre-industrial society also had a different authority structure from industrial society. In pre-industrial society, authority was largely personal, arising from the nature of relationships. This is essentially impossible for us to comprehend today, but one example does remain: the authority of parents over young children. Why do I have authority over my son Alex? Because I am his father. In virtually every other context other than the family itself, industrial era authority is bureaucratic. It is based on boxes in an org chart, with the person occupying the box filling the role, in theory based on competence. Hence, meritocracy comes to be seen as the justification for occupying a role of authority, rather than personal relationship such as father-son, king-subject, lord-vassal, elder-congregant, etc. Nepotism, for example, is disparaged.

From Industrial to Post-Industrial Society

Not everyone classifies the shift to a post-industrial society as a fundamental shift, but I do because of how radical it has been in many ways. It’s not easy to identify why it all happened. Why did the upheavals of the 60s occur? I don’t claim to know. But I will venture a speculation – and I repeat, speculation – with regards to the economic changes.

One key event was the end of the great era of American growth in 1970. This story is told in Northwestern economist Robert Gordon’s book The Rise and Fall of American Growth. (See Paul Krugman’s review for a précis). Gordon argues that once-in-history inventions like electricity and the internal combustion engine powered a century of transformational growth. That era ended around 1970 as we ceased finding similar game changers (computers were not nearly as impactful), and we entered a new era of low productivity growth. At the same time, we hit the beginning of the baby bust in the early 1960s, demographically transitioning to a much smaller Generation X that would, in time, cause labor force shrinkage.

Without growth, industrial society does not socially function and faces crises. Look at the Great Depression, or the problems of the slow growth era since 2000 that have destabilized institutions in the US and Europe. Hence there was a need to keep the growth rate up despite a lack of game changing inventions and weak demographics. How do to that?

You can’t force new inventions, but you can do demographic tricks. One was the Immigration Act of 1965 that removed the 1920s era immigration restrictions and restored very high immigration levels. Today there are over 44 million foreign-born people in the US today, not including the US born descendants of post-1965 arrivals. Add those in and it’s likely tens of millions more.

The second and more immediately impactful change was to migrate women from the home to the workplace. This required a significant restructuring of the family and society of accomplish. It required ending, or beginning the process of ending, the sex role division of labor. And it involved moving from a patriarchal to an egalitarian gender structure.

With the wife no longer present in the home, remaining household production needed to be moved to the marketplace. This had the added benefit of producing “synthetic GDP.” Production that occurs in the household, if not ultimately traded in the marketplace, does not count as GDP. So when a mother stops providing childcare to her own children and pays someone else to do it, GDP goes up. Today daycare is a $48 billion industry that employs 1.6 million people. Unpaid childcare provided at home counts for zero. This helps explain why any form of uncompensated household labor, even “uncompensated emotional labor,” is roundly denounced in our society – it reduces GDP. So we replace the stay-at-home mom with a nanny or daycare center, stop cooking at home and start eating out or order delivery, stop having older couples at church provide mentoring and start hiring marriage counselors, etc.

With even the greatest of efforts, having children interrupts the careers of women, so maximizing female productive capacity requires reducing the number of kids via birth control and abortion. Chelsea Clinton recently said, “It is not a disconnected fact – to address this t-shirt of 1973 – that American women entering the labor force from 1973 to 2009 added three and a half trillion dollars to our economy. Right? The net, new entrance of women – that is not disconnected from the fact that Roe became the law of the land in January of 1973.” She is 100% correct.

It’s not just that there were fewer children overall and more children in daycare, but the upbringing of children was increasingly overseen if not directly implemented by the marketplace and the state. Universal Pre-K is a recent example of this. My neighborhood has places offering pre-pre-K and there are tons of classes for babies and toddlers. There’s a growing program in NYC and other global cities called “Chess at 3.” Parents today rely on classes and professionals rather than themselves to entertain and train kids, even for extremely young children. They increasingly provide just partial financing and transportation to their kids’ organized activities.

The household is thus reduced in function even further, and with an egalitarian gender system increasingly it is hard to distinguish a marriage from roommates or friends with benefits, etc. Unsurprisingly, we see the rise of post-familialism. It’s estimated that a quarter of Millennials will never marry. Many others will never have children. The low birth rate trend is far more advanced in Europe and high income Asia than in the US – some researchers estimate up to a third of women in some East Asian countries will never have kids – but most advanced countries have a birth rate far below replacement. They are entirely dependent on immigration for demographic growth. In effect, the developed world offshored not just production but also reproduction.

One final means by which growth has been maintained is through taking on of huge quantities of debt at all levels, from individual credit cards and student loans to federal government bonds ($21.5 trillion of them at present and growing by the day).

Finally, I’ll point out the direct change in production. We’ve shifted primarily from the production of goods to the provision of services, thus going post-industrial. This helped facilitate the entry of women into the workforce by rebalancing occupations away from male dominated physically rigorous blue-collar occupations. And no longer do we have large vertically integrated companies doing everything soup to nuts. Instead we have globally networked production. Teams of people, factories, software systems, etc. collaborate across firm and national boundaries on a global basis to produce goods and services. This is increasingly facilitated by software, which is creating a nascent shift in the authority structure from bureaucratic to what I call “impersonal.” The algorithm is an example of this. Uber drivers don’t have a boss as we understand it. They are directed by algorithms. As AI increasingly mediates our interactions, expect much more of this.

Not every change in our society is due to the need to keep up growth rates. And again, my story is somewhat a speculation on the Why question. But clearly we see radical changes in our household structures, sex roles, the economy, debt levels, immigration rates, female labor force participation, child bearing and rearing, etc. These are all pretty much indisputable points. This is the backdrop against which the neoliberalization of sex and relationships that I mentioned in Newsletter #21 took place. That neoliberalization is fundamentally an artifact of the transition to post-industrial society.

Summary of the Two Transformations

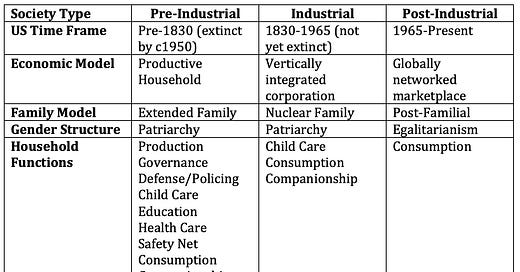

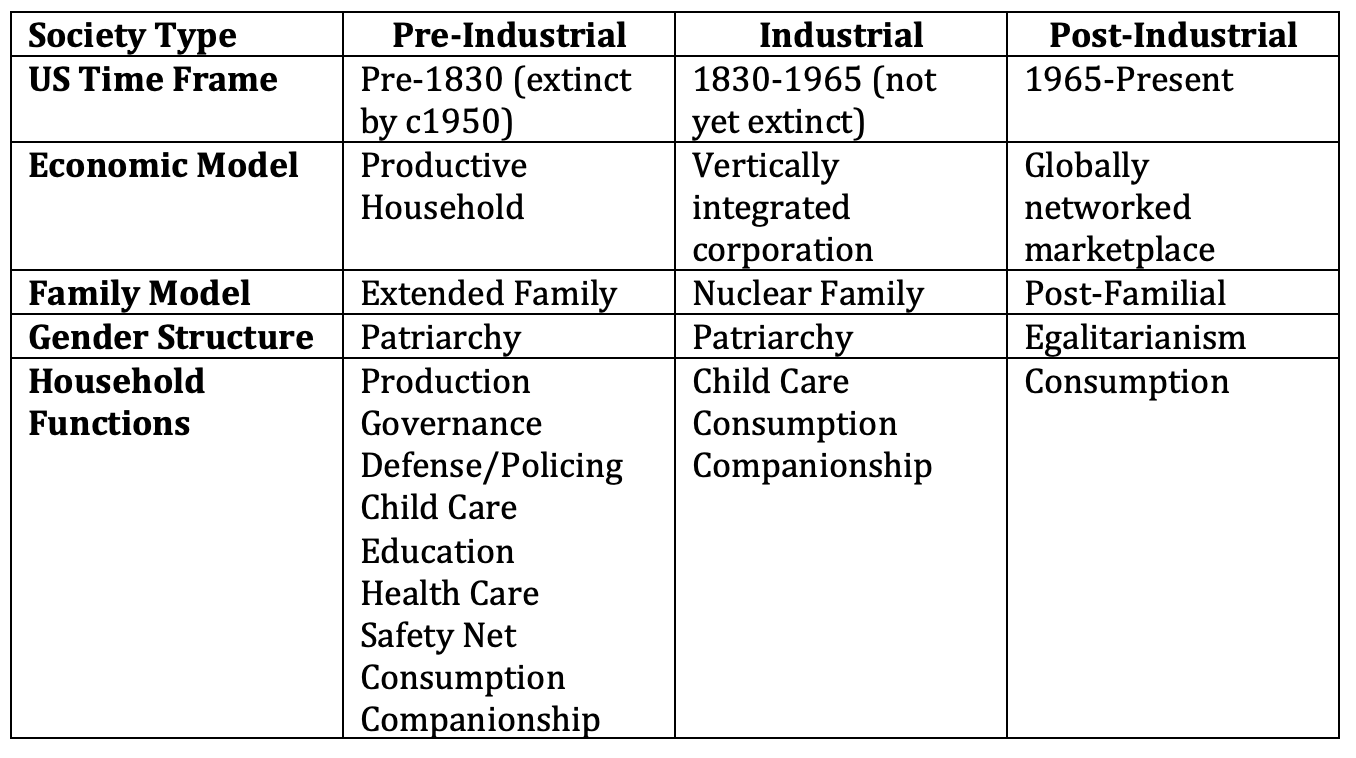

The chart below summarizes the points I just reviewed. It’s not a comprehensive list of differences between these societies, but encapsulates the important points for our purposes.

The post-industrial items are not at full-flower yet and may never be, but they are emblematic trends of the era.

The Church and Societal Change

Today in the secular sphere, to the extent that people talk about the challenges or failures of the transition to modernity, the aim is almost always at the Enlightenment or political philosophy (or maybe secularization). Patrick Deneen’s recent book Why Liberalism Failed is a perfect example of the genre. But China is a non-Western, non-liberal society that’s seeing many of the same transformations as us. Even if we restored the divine right of kings, it would not address the many problems created by industrialization and its aftermath. These challenges are much more rarely discussed.

Inside the church, we often hear pastors talk about changes in society going on today or in the very recent past. I almost never hear them talk about these fundamental shifts, especially from pre-industrial to industrial, and how they have radically altered the nature of marriage, family, and even the church. To the extent that Christians or others do talk about this, most of what I’ve seen proposes some type of communitarian localism à la Tocqueville as a response. That may be a start but is woefully inadequate to the scale of the challenges posted by industrial and post-industrial society.

The chart above represents a big challenge to the church in important fundamental respects. For example, we have to figure out what the instructions and stories in the Bible mean to us today. Again, the entire Bible was written against the backdrop of pre-industrial society. But we live in industrial and post-industrial society. Here’s a question to ponder as a thought experiment.

How many Christian pastors, theologians, writers, etc. can you name who promote ideas about the sexes, marriage, and family that would be strongly rejected by (or even be offensive to) both industrial and post-industrial societies? Or to put it another way, do you know any pastors, etc. advocating any distinctly pre-industrial idea about the sexes, marriage, or family?

I can name maybe one or two. I’m guessing you can’t name many either, if any. I don’t think it proves anything, but it’s an indicator that we might possibly be reading modern cultures into scripture. We are so completely alienated from pre-industrial culture today we can’t even really relate to it. It’s too bizarre for us to take seriously even though it’s the culture of the New Testament church. We preach about the type of community the church is suppose to represent and bemoan that we don’t seem to have it today, but never seem to put 2 and 2 together to understand that the New Testament church was created in an era of thick community while we live in one that is not only typified by thin community, but which is also fundamentally hostile to any forms of thick community. We haven’t grappled with what it means to try to build the kind of church called for in the Bible in today’s world, or even considered whether or not it’s really possible without some sort of complete withdraw à la the Amish.

A second challenge is that in industrial and post-industrial society, marriage and family is incredibly structurally weakened. Today the household is basically about companionship and consumption – and we’re going to consume whether we are married or not. This puts enormous pressure on the companionate bond between husband and wife to sustain the marriage. Their emotional bond becomes the core of the family. But all human relationships have rough patches over the long term. This means every marriage will face repeated moment of crisis during those times. No wonder there are so many divorces. Being emotionally on the outs with your spouse poisons the only real thing the marriage was providing in the first place. By contrast, in the pre-industrial era there was no food, no clothing, no one to take care of you when you were sick, no one to care for you when you were old, etc. if you were not part of a household. That’s why the Bible shows so much concern for those like the widow and the orphan marooned outside the household system. Today, your life outcomes are still much better if you are married, but people are far less dependent on the household to sustain their lives than in previous times.

The best Christian presentation of the challenges posed to the family by industrial society is by Stephen B. Clark in his landmark 1980 opus Man and Woman in Christ. He calls industrial society “technological society” and notes a slew of problems in it facing the family in terms of isolation, emotional bonds, child rearing, and the role of men and women. He writes:

[T]he nuclear family life tends to be unable to carry the heavy burden for personal and emotional support that technological society lays upon it….Technological society is dominated by functional situations which demand much from the individual and give little in return. Since the kinship network is no longer strong enough to assist and the other stable relationships groupings have weakened or vanished, the conjugal family must shoulder the full burden of this support. In addition, the absence of other family functions tends to make this one function the focal point of family life. This emotional intensity produces a strain on the conjugal family which it is not always able to cope with.

…

The position of the family within technological society is precarious. It performs essential functions for the wider society, but in so doing it must operate according to a principle of social structure diametrically opposed to this society. Consequently the family undergoes serious tensions, and its future in technological society is in doubt.

Interestingly, one of the divides in the church I highlighted back in Newsletter #13, that between the “positive” and “neutral” world Christians, seems to follow these cleavages. Roughly, the positive world church embraces an industrial era paradigm (while adopting a few post-industrialisms) while the neutral-world church embraces (with some reservations) a post-industrial one. I will point out one substantive challenge to each of these groups to get people thinking about the topic.

The positive world church sees clearly the negative implications of post-industrial society, but fails to appreciate that the industrial era, with non-productive nuclear family households stripped of most of their pre-industrial functions, also has problems. One specific area they have have not seriously addressed is the role of women. The pre-industrial era had a strong sex role division of labor, but the woman also had a significant and highly valued productive capacity in the home. For example, in the famous passage in Proverbs 31, the husband is at the gates of the city, fulfilling his role as head of household in civic life. This wife is at home, but there is helping to administer a vast household enterprise. In industrial society, the wife is reduced to a homemaker. This may have suited some women temperamentally or during certain stages of life such as when caring for young children, but it provided limited opportunities for women with high IQs or an orientation towards production to put their talents to use. This was part of the complaint of the early second wave feminists. The industrial era non-productive housewife who focuses on childrearing and keeping house is itself a historic anomaly. (The male’s industrial era role, in which he is predominantly away from the home, also brings problems).

Ultimately the Baby Boom generation reared in the 1950s industrial nuclear family rebelled violently against it, providing at least a prima facie case that something was wrong.

The neutral world church tends not to have thought much about these transformations either, other than at a facile level (e.g., equating the household productive function of women in Biblical times with women working in an office today when neither husbands nor wives in that era worked in a job as we know it). They critique industrial era marital and sex role norms, correctly in some cases, but mostly for the purposes of adapting themselves to post-industrial ones instead. They see their role as mostly one of adapting to rather than challenging or attempting to shape societal changes, many of which they see as positive. They tend to share contemporary society’s view of the past as a benighted age.

For example, it would appear that the neutral world church is in the process of redefining their theology of the church to make it more explicitly non-familial. We see this clearly in the attacks on “making an idol out of the family.” Or those saying that Christians have a “prosperity gospel” view of the family. Or in the stressing of singleness as a valid Christian calling and calls for the church to be more accommodating to singles. These churches, especially the urban ones, face the real problem that many of them have congregations that are majority singles. How to handle that is a difficult pastoral problem. From what I’ve observed they are taking the easy way out by embracing a form of post-familialism.

My guess is that they will in effect say that the family of God is the real family, not earthly family, and that too think too highly of the earthly family is sinful. This will be presented as being more faithful to scripture and the early church, as opposed to the worldly family paradigms of the 50s that had been normative for the church. They won’t be wrong in criticizing the 50s, but their theology will be more reflective of contemporary society than the early church. We won’t hear much of Paul’s instructions to women from the pastorals, such as that widows under age 60 should remarry, for example. Nor of things like the Westminster Large Catechism’s inclusion of “undue delay of marriage” as a violation of the Seventh Commandment (Q139).

This will be a failure even if it succeeds because post-familialism is over the long run usually harmful to the individual (as folks like Brad Wilcox have tirelessly documented) as well as society. You’ll note that the US elites have by and large insulated themselves from the most harmful consequences of post-industrial society. They still tend to ultimately get and stay married (the only segment of our society that does). They tend to have children. They don’t practice sexual libertinism or advocate it for their children.

In fact, it’s interesting how often the behaviors of certain segments of the elite resemble pre-industrial society. Political families, for example, are essentially household enterprises. Hillary Clinton and Michelle Obama were not just homemakers, they were key co-producers in their husbands’ political careers, then ultimately their own endeavors. Children are often brought into the family business. In some political dynasties we see a true multi-generational extended family business, as with the Kennedys and Bushes.

Pastors often do the same. Pastors, even urban ones, are overwhelmingly married, often marrying young. They tend to have bigger families. The pastor’s wife is generally a critical contributor to church life. They sometimes live onsite in a parsonage. And they also often bring their children into the business. Think about Brian and Bobbie Houston of Hillsong. They built the church as a couple. Their son Joel is a key songwriter and member of the Hillsong United band, and co-leads Hillsong NYC. Another son leads Hillsong Los Angeles. Their daughter is involved in youth ministry in Australia.

The frequent involvement of children in political and pastoral businesses is interesting given societal taboos on nepotism in an age of meritocratic bureaucratic authority. I’m not complaining. I think these people are following a very healthy model. They found a way to incorporate some of the strengths of the pre-industrial household into their lives in a way that is compatible with the modern world. I just wish they touted it more.

Regardless of what they might say about post-familialism for others, they sure aren’t buying it for themselves. No many how much they talk about how their marriages remind them of just how much sanctification they still need, they wouldn’t trade their own family for all the gold in Ft. Knox. As always, watch what people do much more so than listen to what they say. What’s more, if marriage is the paradigmatic symbol on earth of the union between Christ and the church, what does it say when a Christian community abandons marriage as the normative institution in which to build a life?

So what should we do? I don’t know. But we need to think about this much more seriously and deeply. We need to look at how the theology of the Bible does or does not embed pre-industrial social forms. We need to stop holding up the 1950s suburban family as the Platonic form of the family. But nor can we embrace a post-familial vision for the church. We should be less invested in the cultural norms of both industrial and post-industrial society, and be open to things that might conflict with both. We cannot go back to pre-industrial society, but what can we do to more authentically live out God’s word today, and to mitigate some of the biggest deficiencies of the industrial and post-industrial household structures and sex role norms, in a way that works for today? How should we engage with, or against, today’s societal forms? These aren’t easy to figure out, but it’s critical to do.

Noteworthy

London Review of Books: “Marriage as an institution will not last for ever. Not in China at least.”

Punishment won’t get more babies from Chinese women. I’m not sure even Scandinavian-style policies on childcare and parental benefits would boost the birth rate. After more than thirty years of the one-child policy, urban women are used to having the same professional opportunities as men, and have proved equal to men in all areas. It’s not likely that these women would willingly give up their careers and become housewives again.

Coda

I have a follow-up on the friend zone. In my last edition, I cited a passage from Tim and Kathy Keller’s book The Meaning of Marriage about Kathy’s wise decision not to inhabit the friend zone. I forgot to include this other excellent passage on “cheap girlfriend syndrome”:

Kathy and I observed this phenomenon while still in college. We dubbed it the “cheap girlfriend syndrome,” because it most often was the woman who was interested in marriage while the man was not. Sometimes a man and a woman would spend a great deal of time together. This meant the man had a female companion to accompany time to events (when he wanted one), a woman to talk to (if he felt like talking), and a supportive listener (to his troubles, should he need to unburden himself). If the relationship did not involve sex, the man would insist to others that he and girl weren’t even dating, that they weren’t “involved.” If she ever chanced to question this, he might protest: “I never said we were more than friends!” But this is unfair, because they were more than friends. He was getting much more than he would out of a male buddy relationship. He was getting many of the perks of marriage without the cost of commitment, while the woman was slowly curling up and dying inside.

Since this newsletter is for men, be sure to also reverse the genders and apply accordingly. (While the man is perhaps more often to blame for not being willing to move forward if the couple is formally dating, I would argue that when it’s a “weren’t even dating” situation it’s more likely the woman). This is the essence of the friend zone.

Ladies, if he won’t give you a ring, don’t sleep with him, much less move in with him!