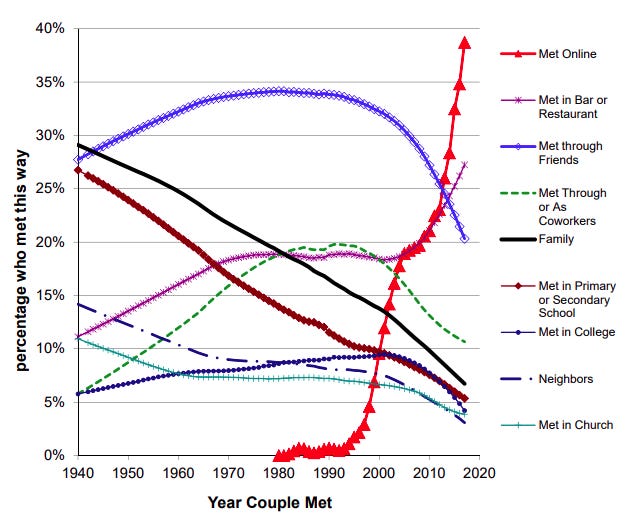

There’s been a stupendous increase in the share of couples who meet online, along with an uptick with those meeting in bars. Every other way apart from in bars that couples meet has been losing share. This chart says it all (h/t @JSMilbank):

Because online dating is now so dominant, we have to ask how singles should respond to this new reality.

First, we have to understand the facts of online dating. Because these sites are digital, they have hard data about user behavior. That lets us get an objective look at how men and women actually behave in the dating market in the real world. We have to know this information and be willing to accept it, because it’s absolutely a picture of reality.

Second, if you are a single man, you need to understand how you approach online dating. Online dating in effect represents the “globalization” of the dating market just as previously happened with the economy. And the results are similar, with extremely high inequality of outcomes. Online dating also skews heavily towards looks, which favors the very attractive.

Realities of Human Behavior Revealed by Online Dating

One of the key pieces of data that’s been examined is what drives attraction on online dating sites. This can be done at the macro level or the micro level. For example, the way users rate others varies by race, according to multiple reports. OkCupid, for example, found that blacks and Asian men were penalized by users. (A recent book says the black women in particular are discriminated against).

And at the micro level it’s also been discovered that having a cat in your photo makes heterosexuals be seen as less attractive, a 5% lower like rate for men and a 7% lower like rate for women. A photograph with a dog increases your like rate (20% for men and 3% for women).

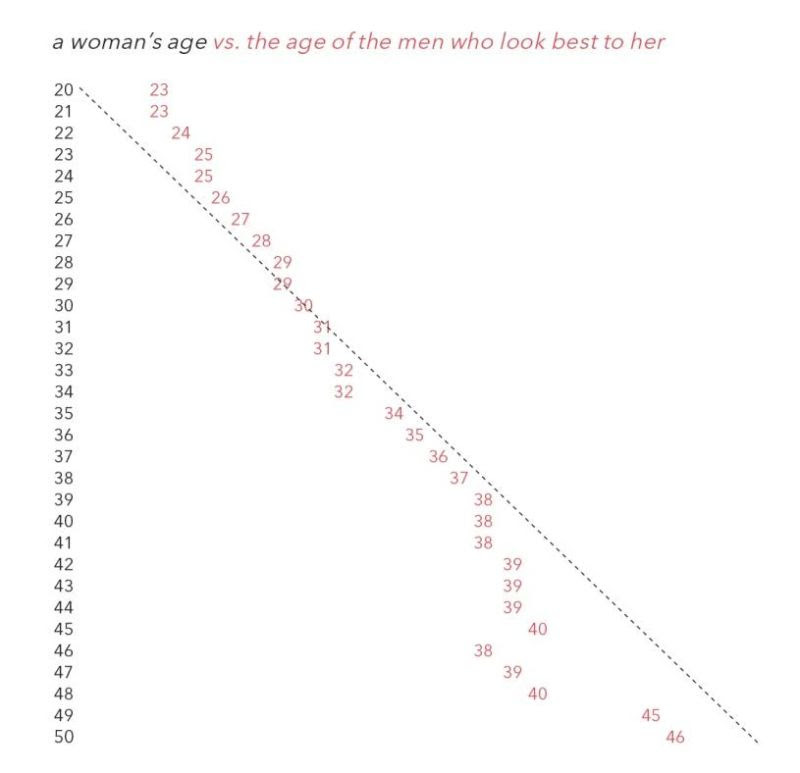

One of the keys is how attractiveness varies by age. Another previous study from OkCupid, as reported by the feminist web site Jezebel, showed that the age of the men that women find most attractive scales roughly linearly with the woman’s own age:

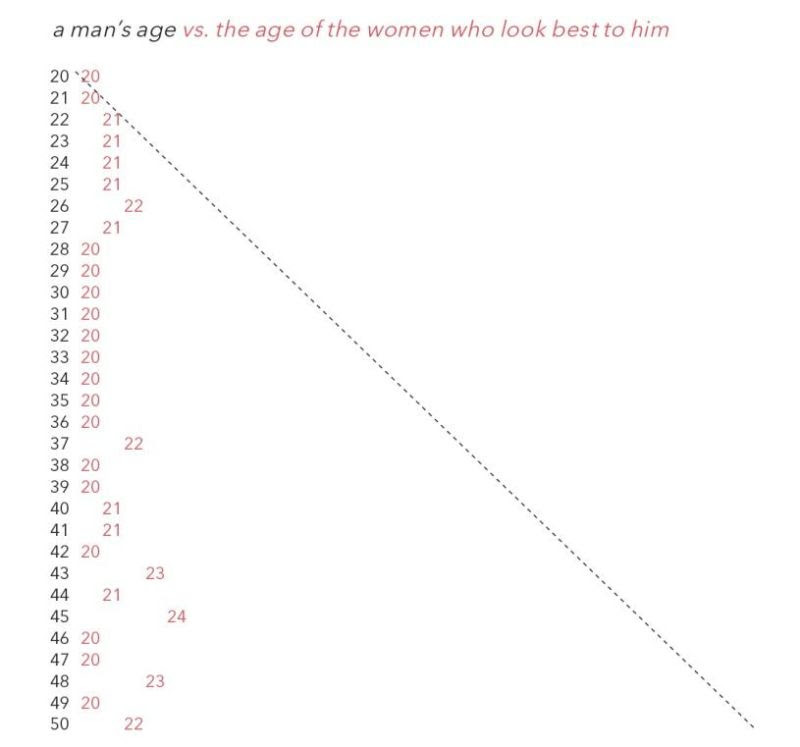

But for men, it’s radically different.

No matter what their age, men think women in their early 20s look best. Here was Jezebel’s commentary on this:

A woman’s at her best when she’s in her very early twenties. Period. And really my plot doesn’t show that strongly enough. The four highest-rated female ages are 20, 21, 22, and 23 for every group of guys but one… Younger is better, and youngest is best of all, and if “over the hill” means the beginning of a person’s decline, a straight woman is over the hill as soon as she’s old enough to drink.

This shows yet again that men are overwhelmingly attracted to looks and youth in women.

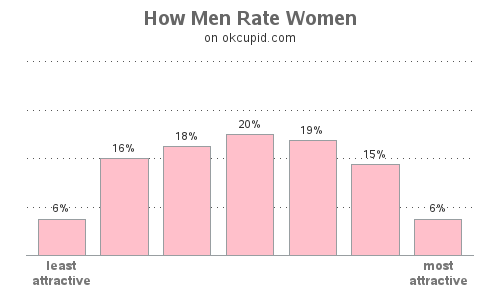

But there are other ways to look at this. A researcher at the company that produces the statistical analysis software SAS looked at the distribution of ratings of attractiveness given out by men and women. Here is the distribution of how men rated women:

As you can see, this resembles a bell curve, which is what we would expect. Most women are rated near average, with fewer at the two extremes.

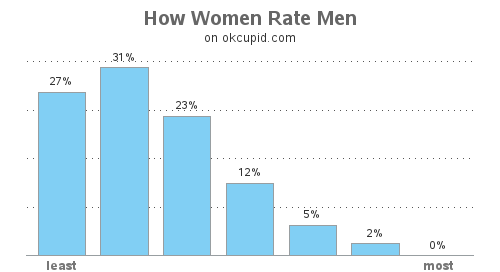

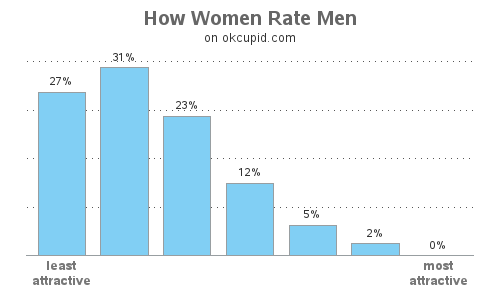

By contrast, here is how women rated men

Women rate 81% of men below average and only 7% above average. Brutal.

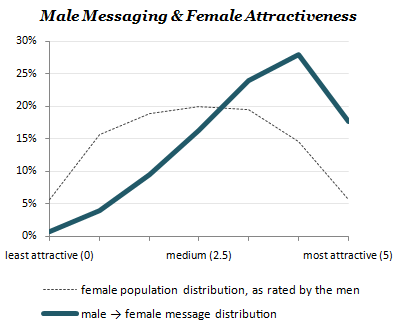

This does not necessarily determine whether men and women message each other however. OkCupid overlaid messaging rates on top of these same attractiveness distributions. Here’s a chart of the distribution of how men rated women and who they messaged:

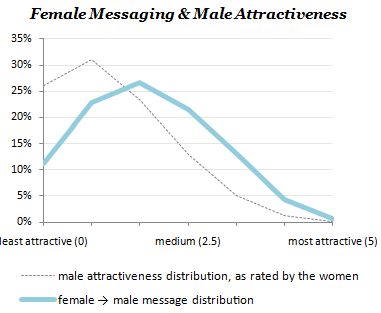

And the same chart for women:

In short, men seem to shoot for the moon in terms of whom they message, whereas women rate men very harshly but message men on a sort of curve grading system. As the OkCupid blogger put it, “The average-looking woman has convinced herself that the vast majority of males aren’t good enough for her, but she then goes right out and messages them anyway.”

Nevertheless, these dynamics translate into extreme inequality, especially for men. A Medium user did a statistical analysis of Tinder. His conclusion was that, if you are a man, “unless you are really hot you are probably better off not wasting your time on Tinder.” He showed that inequality of interest on Tinder is higher than income inequality in the United States. Here is one of his charts:

There are a couple of other great charts on that post, so I suggest clicking over to look at them. He observes:

As I stated previously the average female “likes” 12% of men on Tinder. This doesn't mean though that most males will get “liked” back by 12% of all the women they “like” on Tinder. This would only be the case if “likes” were equally distributed. In reality, the bottom 80% of men are fighting over the bottom 22% of women and the top 78% of women are fighting over the top 20% of men….A man of average attractiveness can only expect to be liked by slightly less than 1% of females (0.87%). This equates to 1 “like” for every 115 females.

Aviv Goldgeier at Hinge found similar levels of inequality on that app. He calculated the inequality of likes using the Gini Coefficient, which is a common measure of income inequality in which 0 is perfect equality and 1 is perfect inequality. Here is what he said:

As it pertains to incoming likes, straight females on Hinge show a Gini index of 0.376, and for straight males it’s 0.542. On a list of 149 countries’ Gini indices provided by the CIA World Factbook, this would place the female dating economy as 75th most unequal (average — think Western Europe) and the male dating economy as the 8th most unequal (kleptocracy, apartheid, perpetual civil war — think South Africa).

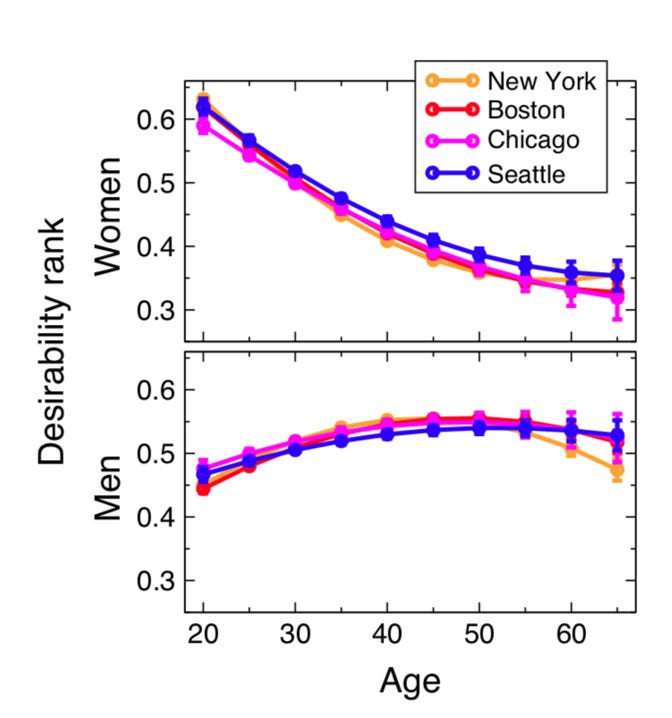

Lastly, I’ll share a chart about how relative attractiveness changes over time. This is from an academic study reported on by the Atlantic. Researchers used Google’s page rank algorithm to rate the attractiveness of men and women on an undisclosed dating site in four cities. Here’s how relative attractiveness changes by age:

I previously wrote about the “attractiveness curve” for men and women. Women are on average considered more attractive in their 20s (especially their early 20s). But around age 30 the script flips and men are on average considered more attractive, a situation that persists for the rest of their lives.

This chart is that curve statistically demonstrated. If they were on the same chart, the male and female lines would cross about age 32.

This has profound implications, obviously. It explains why men are apt to complain about difficulties in finding a woman while in their 20s, while you tend to hear similar complaints from older women, especially those ages 35+. Women are in a sense holding the cards when they are in their 20s, but, perhaps unfairly, if they don’t get married to a man before or soon after those lines cross, they can find themselves in real trouble when it comes to getting married.

Again, all of these charts are based on actual behavior by real people on actual online sites and analyzed based on hard data downloaded from them.

Implications of the Rise of Online Dating

I previously wrote about the neoliberalization of relationships. Today, relationships are essentially formed in marketplaces. In the past, to the extent that there was a market, it was a marriage market, with dating serving as a funnel into it. Now there are multiple marketplaces: a sexual marketplace, a dating marketplace, and a marriage marketplace. Unlike in the past people can now choose relationships free hookups, casual dating, long term relationships, or marriage. And people can jump from one marketplace to another anytime they want (though our society still has social rules against married people cheating without getting a divorce first).

Online dating represents a true marketplace form. Everyone in the online dating market is simultaneously a product and a potential buyer. And we see from the data above how that sorts out in terms of how that marketplace functions.

But there are other considerations to keep in mind.

First, online dating is functionally equivalent to globalization in trade. Pre-globalization, most countries traded internally. Goods and services consumed domestically were typically produced domestically. Obviously there was some international trade, but it was small relative to the whole, and cumbersome in many cases.

With global trade deals like the Uruguay Round of trade talks (which created the WTO), improved global logistics, global broadband and the internet, industrialization in places like China and elsewhere, we now have a world of much more broad-based global competition. Today a domestic manufacturer competes not just against other domestic manufacturers, but with manufacturers all over the globe.

What this did in many cases was to merge what used to be independent national or local hierarchies into a single global hierarchy. This meant major change in who was a winner and who was a loser. The top global competitors became stupendously successful. Many former national or local champions found themselves in newfound competition with better or much, much cheaper competitors and took a big hit.

Online dating acts in a similar manner. It used to be that men and women met each other within various physical spaces and social circles in the real world: school, work, church, family friendship circles, neighborhoods, etc. You could certainly meet someone outside of that, even intentionally such as by looking at old school print personal ads. But the market you were in was much more limited.

Because every school, neighborhood, church, etc. was in essence its own market, that meant they each had their own local marketplace winners. And people would sort of match up within that based on their relative value in the market.

But with online dating, all those old local relationships markets have been merged. It’s not true globalization because most people don’t want to date someone on the other side of the world or the country. But in most places it’s certainly the metropolitanization of dating. Here in Indianapolis, for example, online dating means you have access to all the singles on those sites in a region of over two million people.

So in an online dating world, you are no longer just in competition with people in your social circles. You are in competition with everyone in your city or region. It may be true that your pool of prospects is also bigger. But the dynamics of these global type markets have in practice tended to produce more extremes of winners and losers.

Remember the stats I posted above from sites like Tinder and Hinge showing extreme “income inequality” in the online dating market. High levels of inequality for men is a basic feature of how online dating functions.

If you are a top 10 to maybe 20% type guy, then this situation may be good for you. But if you’re not, it’s potentially bad.

Secondly, online dating skews very strongly towards looks as an initial screening criterion. This is particularly true on swipe apps like Tinder. Nobody has time to wade through all the singles listings in their area, and that tends to promote heavy filtering. And after setting filters like age, etc., the easiest and quickest thing to filter on is looks. Apps like Bumble even severely restrict the amount of text you are allowed to put in your profile.

As it happens, men’s attraction to women is heavily based on looks. But women’s attraction to men is based on a broader set of criteria: power and status, confidence and charisma, looks and style, and resources like money. In fact, looks are often not the dominant driver of attraction.

So if you are a very good looking guy, online dating may work in your favor, because you are going to draw a lot of engagement. But if your biggest strengths are in other areas, if you are not in the top 10-20% of guys in looks, you are going to be at a disadvantage in online dating.

Lastly, on traditional online dating platforms (other than Bumble), women are besieged with responses. Many of these are spammy or otherwise low quality. I’m sure some border on or actually are harassment. But even so, the medium is the message: the sheer quantity of responses is sending a signal to the person receiving them that she is very attractive and desirable. Think about how it would affect you. What would you think if you created an online dating profile and immediately dozens of people started emailing you? Even if you weren’t interested in any of the people, the quantity at some level is very gratifying. As an infamous person once said, “Quantity has a quality all its own.”

This creates two challenges for you as a man. The first is being able to cut through all the noise and get noticed among all the other messages she’s getting. The second is having her judge you versus an assessment of her own attractiveness that’s potentially artificially boosted by the online dating system itself and the immense amount of inbound attention it generates for her.

In my view, these three factors – the globalization effect, the looks-skewed environment, and the dynamics around responses to women – make online dating an unfavorable environment for most men, especially for those outside the top 10-20% in looks.

Now, online dating has worked for lots of people. I know men who met their wife via online dating, which is great. I don’t look down on anyone who uses it. I view it strictly as a tool. The question is whether it’s an effective tool. If you think it’s a good tool for you, then by all means use it. A reader said that for him, online dating was a “force multiplier” that let him find more potential matches than he otherwise would have been able to. He successfully got maried via online dating. For me, I made the decision to stay completely off online dating platforms.

What are alternative strategies to online dating?

Well, it’s to go back to the physical spaces and social communities of real life, to more localized markets. There’s no substitute for walking up to a woman you are interested in and asking her on a date. Yes, there’s a risk of rejection. Yes, there’s a risk she might say you made “unwanted advances.” But as a man, if you don’t have the confidence to face that kind of risk, you have bigger problem than getting dates. And again, the medium is the message. The mere fact that she sees you have the confidence to interact in the real world is powerful.

And let’s be honest, if you struggle with women in the real world, going online is not likely to be the solution. At some point she’s actually going to meet you in person, after all.

In the real world, it’s also possible to operate in situations that put your best foot forward with women. I’ll give you an example from my own life. I had dated my wife in Indianapolis shortly before moving to NYC. I was not in a position to be in a serious relationship at that time, so I broke things off when I moved. When I was in a position to be in a serious relationship, I decided to reengage with her. I did it on a trip back to Indiana when I was scheduled to be the keynote speaker at a local chamber of commerce annual luncheon. I invited her to attend it and see my talk.

Remember, women are interested in status, confidence, etc. When I got up on the stage as the main event speaker, that’s status and she saw it. She saw it when I confidently, competently, and with mastery of my subject gave a 30-minute keynote presentation in front of hundreds of people.

This environment, unlike online dating, maximized my best assets as a man. There’s no way to convey the visceral reality of seeing me speak in front of a sizable crowd into an online dating profile or even a video of the event.

As it happens, I had good reason to believe she’d be interested anyway, but every little bit helps. She sold her house, moved to New York, and we were married four months later.

The key is that you want to be in a local relationship marketplace (physical spaces and actual social circles) rather than the global marketplace of online dating. And you want to find those local places and social circles where your best attributes shine through and where you can become one of the top men there.

However, if you do decide to use online dating, you need to find ways to operate that take account of all the dynamics I laid out in this newsletter.

Bookshelf: Exit, Voice, and Loyalty

People keep asking me to put together a recommended book list. And while I don’t have a list put together, I will periodically share books that I’ve enjoyed and benefitted from. I’ll focus on those that are easy to read and of reasonable length.

One is Exit, Voice, and Loyalty: Responses to Decline in Firms, Organizations, and States by Albert O. Hirschman. This is one of the most famous books about the choices facing people unhappy with institutions they are involved with, and what the implications of those choices are.

The two basic options are Exit – to leave, often switching to a new institution. And Voice – to complain, lobby, or otherwise try to prompt the institution to reform. (Loyalty refers to how these options are modified in the presence of loyalty to institutions).

The first chapter is a bit dull, but otherwise the book is brimming with insight and is eminently quotable. See the Coda below and Newsletter #24. In an age of institutional decay, this book is well worth reading.

If you like it and would like to check out other books by Hirschman, try The Rhetoric of Reaction, which is about the ways conservatives frame their arguments. Or pick up The Passions and the Interests, which traces the intellectual history of how human desires (passions) went from being seen as a source of evil to being seen as good after being recapitulated as “interests” (most notably in the form of Adam Smith’s invisible hand).

Coda

The traditional American idea of success confirms the hold which exit has had on the national imagination. Success – or what amounts to the same thing, upward social mobility – has long been conceived in terms of evolutionary individualism. The successful individual who starts out at a low rung of the social ladder, necessarily leaves his own group behind as he rises, he “passes” into, or is “accepted” by, the next higher group. He takes his immediate family along, but hardly anyone else. Success is in fact symbolized and consecrated by a succession of physical moves out of the poorer quarters in which he was brought up into ever better neighborhoods. He may later finance some charitable activities designed to succor the poor or the deserving of the group and neighborhood to which he once belonged. But if an entire ethnic or religious minority group acquires a higher social status, this occurs essentially as the cumulative result of numerous, individual, uncoordinated success stories and physical moves of this kind rather than because of concentrated group efforts.

– Albert O. Hirschman, Exit, Voice and Loyalty