The Logic of Persuasion

One of the most important things to know about disputes in the modern world is:

If you’re debating substance, you’ve already lost.

That is to say, if you are trying to convince a skeptic or win a debate, including debates over what policies and views will prevail in a church or other institution, by using factual, logical, rational arguments, you are very likely to lose and in fact, have probably lost already and just don’t know it yet.

This is very important to understand because so many people, especially conservatives, default to a logical model of argumentation to the exclusion of all other forms of persuasion or influence.

As I noted in Newsletter #45, ideas may have consequences, but lots of other things have consequences too. For example, arguments that flatter the sensibilities of powerful people and institutions, or tell the audience what it wants to hear, are very likely to prevail even if they are weak. Conversely, true but unpopular ideas often flounder.

Today I want to further explore this problem.

Aristotle’s model of persuasion has three components: ethos, pathos, and logos. Taking them in reverse order:

Logos is rational argument based on facts and logic. When I speak of debating substance, this is what I’m talking about.

Pathos is an appeal to emotion or sentiment.

Ethos is an appeal to character, position, status, or “brand.”

In our modern, mass media saturated society, most winning arguments are only nominally based on logic. Instead, emotional based appeals are much more key. But above all the position or status of the person making the arguments trumps all. It determines to a great extent, for example, which arguments or emotional appeals are considered valid. The battle for social or cultural status ends up being definitive today in all too many cases.

The nature of logical argument is self-evident, but I will say a bit more about pathos and ethos.

An Example of Pathos

A good example of an appeal based on pathos is this twenty minute video by Mary Beth McGreevy defending the complementarian gender system of the Presbyterian Church in America. In complementarianism, women are not allowed to serve in a pastoral position. Her defense of this system is based on how it makes her feel and what it allows her to do. She’s attempting to assuage the possibly negative feelings of her female target audience towards the complementarian system, and to argue for applying complementarian doctrine in a minimalist manner.

Note how often she uses variants of the word “feel” in this video:

“I started talking to women who felt hurt”

“I’d always felt so affirmed”

“I’ve always felt heard, like I had a place at the table”

“I realize not all women have felt that way”

“Let me tell you how that makes me feel as a woman”

“It feels like I’m driving down the road”

There are many more occurrences of the word “feel” than these. Not that she makes no logical, theological arguments to defend complementarianism at all. Her video is designed to complement, as it were, that form of argument by engaging in a different way.

Is this a valid way to try to persuade people? Yes.

Provided you are trying to persuade someone of what you believe to be the truth, there’s no reason not to avail yourself of all the levers of persuasion and rhetoric, providing your techniques are not themselves deceptive or designed to manipulate.

Understanding Ethos

Ethos is a more expansive and complex matter. The simplest component is simply our character or reputation. We aren’t likely to believe someone who is known as a consummate liar, for example. The better our reputation for honesty, integrity, and fairness, the more likely we are to be believed.

Other attributes of a person can also affect his ability to persuade. Robert Cialdini, in his must-read book Influence: The Psychology of Persuasion, notes that social proof and likability are key factors in persuasion, and that similarity plays a key role in their effectiveness. We are more likely to be persuaded by someone we see as similar to ourselves. In that McGreevy video, for example, it’s important that she’s a woman making an argument about women’s roles in the church. That makes her more credible with other women than a man would be. This is one reason pastors often trot out their wives to deliver some of their more unpopular messages on gender.

The credentials or position that we hold (authority) can also help determine whether or not our position is accepted. Cialdini includes authority as one of his six key principles of persuasion. When a medical doctor in a white lab coat sits us down in his office, with his degrees and board certifications prominently displayed on the wall, we are more likely to believe what he says than we are to take health advice from some random person on the street. So powerful is this association that he said that even an actor who merely played a doctor on TV could tap into the aura of that. He cited a Sanka coffee ad from the 1970s that featured actor Robert Young, who had won an Emmy in 1970 for playing the lead character in Marcus Welby, M.D. We can also think of judges, teachers, etc. as having authority based on the position they hold.

Then there’s cultural status, which can be personal or institutional. What is written in The New York Times has a powerful and profound effect on what truths (or “truths”) are accepted in our society. The Times and other elite institutions define cultural reality in the United States.

Sociologist James Davison Hunter said that we should “think of culture as a form of capital, much like money itself.” He further says:

A Ph.D. has more cultural capital than a car mechanic; a member of the national academy of sciences has more cultural capital than a high school science teacher; the winner of a Nobel Prize in literature has more cultural capital than a romance novelist. These are extreme contrasts but you get the point. Like money, accumulated cultural capital translates into a kind of power and influence. But what kind of power? What kind of influence? It starts as credibility, an authority one possesses which puts one in a position to be taken seriously. It ends as the power to define reality itself. It is the power to name things.

Hunter argues that this cultural power resides primarily in networks and the institutions arising from them. And he says that culture changes from the top down, or from the center outward.

With economic capital, quantity is paramount. More is almost always better, and more influential, than less. With cultural capital, it isn’t quantity but quality that counts most. It is the status of cultural credentials and accomplishment. In other words, with culture, there is a center and a periphery. The individuals, networks and institutions most critically involved in the production of a culture or civilization operate in the “center” where prestige is the highest; not on the periphery, where status is low.

This is the most critical thing to understand from this newsletter. If the networks and institutions at the cultural center are relatively united, they will almost always get their way regardless of any emotional appeal, facts, logical arguments, or actual truth to the contrary. Almost no one can stand up against a campaign by the New York Times or Washington Post, for example. This is especially true today when American elites are unusually united on a wide range of issues.

New Calvinism as Culture Power Strategy

In our mass media society, this cultural power often trumps everything else. Attempting to argue about substance in the absence of cultural power is overwhelmingly likely to fail. Those possessing cultural power have no need to even seriously and legitimately engage with the arguments of their opponents. Conversely, people without much cultural power often resort to logical argument because that’s all they have.

The key to having your ideas prevail today is the acquisition of cultural power. This is not a simple matter. Because this power resides in networks, even getting a job at The New York Times doesn’t necessarily do a lot by itself. Ross Douthat is a conservative Catholic columnist for the Times, but he doesn’t have much influence on society as a whole. He’s also highly restricted in what he can say if he wants to keep his position. That’s not to say there’s no benefit to Douthat in being an NYT columnist. It definitely means many more influential people will be reading him than they otherwise would, for example. But a few well-placed people here and there don’t counter entire networks.

But high-status networks exist in multiple domains. There isn’t just one domain with the Times and Harvard at the top. In some cases, those who are attuned to how cultural power works can establish a degree of power over certain subdomains even if they cannot do so at the highest levels of society as a whole.

This appears to be the case with the New Calvinism movement, for example. Sociologist Brad Vermurlen, in his book Reformed Resurgence, uses a model called strategic action field theory to understand that movement. He writes:

The crucial insight from strategic action field theory that helps to explain the New Calvinism is that through social processes of game-like contestation, leaders of movements and organizations strategically battle and vie with their competitors for a more advantageous position in and over their field, which is defined by possession of symbolic capital and power.

Vermurlen cites a wide range of strategic actions the New Calvinist movement undertook. I recommend reading it if you are in the evangelical world, and you should also listen to my interview with him about it.

In my analysis, the New Calvinist movement strategically created networks and institutions of celebrity pastors and other key figures in order to obtain power over a portion of the evangelical subdomain. This notably includes establishing the Gospel Coalition but also many other overlapping networks and institutions. (James Davison Hunter is closely connected to key New Calvinist figures, and it would be interesting to know if he advised them in their strategy).

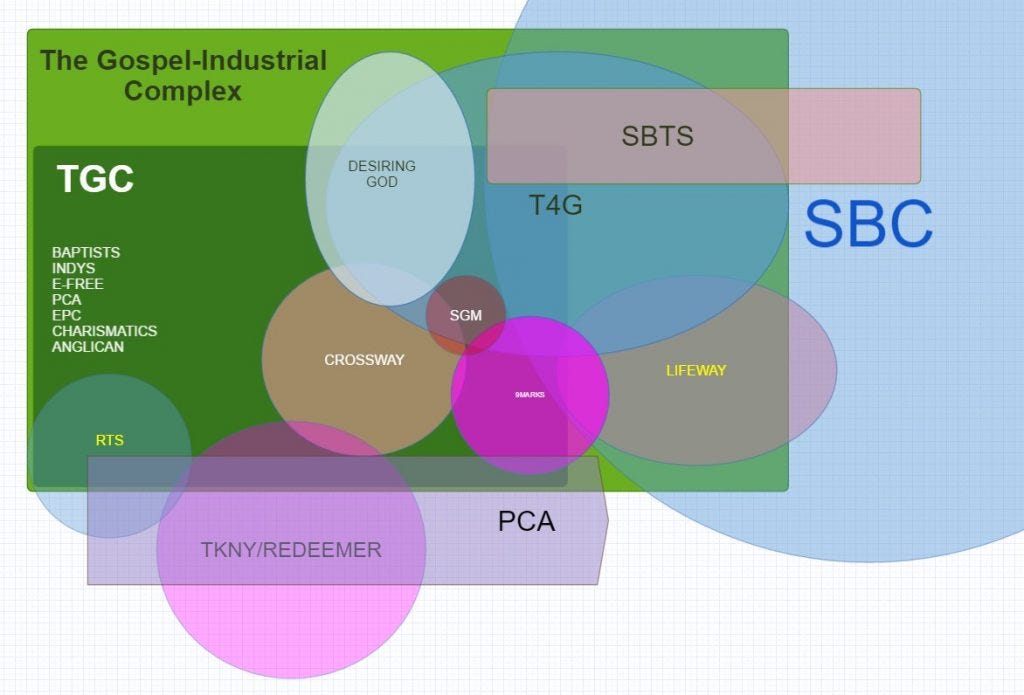

Brad Isbell, a confessionalist Presbyterian who is a critic of the New Calvinists, created this graphic of what he called “the gospel-industrial complex” (Carl Trueman’s “Big Eva” is another popular term) to show New Calvinism’s contours.

While his intent was polemical, this is a broadly accurate depiction of the institutional components of this movement. These networks and institutions give the core personalities of New Calvinism immense power over a key part of the Evangelical world. Vermurlen notes that they used this to establish themselves as gatekeepers (something that Tim Keller agreed was true in a recent podcast):

Several New Calvinist leaders also strategically position themselves as the rightful gatekeepers of their field’s established “orthodoxy,” functioning as if they had real authority to claim which other players are “in” and “out” of the American Evangelical field.

Beyond creating their own networks and institutions, the New Calvinists have also greatly magnified their power through the cultivation of strategic relationships with secular elite cultural institutions, particularly the elite East Coast media. I go beyond Vermurlen in this. He says that the New Calvinists were able to take advantage of media that came their way but I have reason to believe that they’ve intentionally built these relationships as well.

A few of these New Calvinist leaders have ready access to the op-ed pages of the Times, The Washington Post, The Atlantic, and others. They also have good relationships with friendly reporters in their news pages who will generally frame matters in ways favorable to the New Calvinist establishment. (You should be able to readily identify most of these reporters. If you can’t, that’s a sign you need to do some homework).

These elite media relationships are a force multiplier for the New Calvinist elite. If their own networks and institutions aren’t sufficient to deal with a problem, then “air support” from the secular elite media can be called in to bomb their opponents.

The Statement on Social Justice

As one example of the principles I just outlined in action, let’s examine the case of the Statement on Social Justice. The evangelical world, as in society at large, has been riven with debates over social justice, with some arguing it requires more focus, others less. The New Calvinist elite have by and large been friendly to the social justice agenda (or at least not too opposed), which aligns with the secular elite on this matter.

A group of people opposed to the current social justice turn in the church created a document called the Statement on Social Justice and the Gospel to stake out their position. This was a classic attempt to debate substance. It contains a number of specific affirmations and denials based on the signers’ interpretations of scripture. The authors actually do support some of the social justice agenda they felt appropriate, with statements like:

We affirm that societies must establish laws to correct injustices that have been imposed through cultural prejudice.

“Race” is not a biblical category, but rather a social construct that often has been used to classify groups of people in terms of inferiority and superiority

We affirm that racism is a sin rooted in pride and malice which must be condemned and renounced by all who would honor the image of God in all people

We affirm that virtually all cultures, including our own, at times contain laws and systems that foster racist attitudes and policies.

So they attempted to find common ground, but ultimately rejected today’s social justice movement. The key is that this statement was a list of substantive affirmations and denials that represented a form of logical argument.

In many cases, moves like this statement would be ignored by the New Calvinist elite. But the statement was signed by over 10,000 people, including some big names like John MacArthur, which made it hard to ignore. These signatures are a network of sorts, representing people with some degree of influence in the evangelical world. This added an ethos/status play component to the logical arguments of the statement itself, which likely accounts for the fact that some New Calvinists responded to it.

So how did they respond to this statement? I did not see any of them substantively engage with it, in the sense of responding to any of its propositions directly. Instead, some of them sought to discredit the motivations and character of the signers (i.e., diminishing their ethos positioning).

Russell Moore, president of the Ethics and Religious Liberty Commission of the Southern Baptist Convention, compared the signers of the statement to the people who refused to denounce slavery or Jim Crow. For example, in one Fox News podcast he said:

What we’re really talking about is race. We have a long-lasting issue within evangelicalism of people saying, “Let’s not talk about issues of racial reconciliation and unity and justice. That would be a distraction from the gospel.” That’s exactly what was happening in the nineteenth century as it related to human slavery. That’s exactly what was happening in the 1920s and the 1950s as it related to Jim Crow. And it persists among us.

And somebody asked Tim Keller about the statement during the Q&A period of a conference he was speaking at. A video of his response (which has subsequently been removed due to a copyright claim) was posted. Here’s what he said:

It’s not so much what [the statement] says, but what it does. It’s trying to marginalize people talking about race and justice, it’s trying to say, “You’re really not biblical” and it’s not fair in that sense … If somebody tried to go down [the statement] with me, “Will you agree with this, will you agree with this,” I would say, “You’re looking at the level of what it says and not the level of what it’s doing.” I do think what it’s trying to do is it’s trying to say, “Don’t make this emphasis, don’t worry about the poor, don’t worry about the injustice.” That’s really what it’s saying.

This was an off-the-cuff response to a question and probably did not reflect a fully considered and thought-out position on the matter. It was also not officially taped and was captured by cell phone. However, after the video caused a small controversy, he could have issued a clarifying statement. He did not and to the best of my knowledge has never done so, allowing his statement to stand as his take.

Try to ignore the substance of the social justice debate and your own feelings about it, and look only at the mechanisms of debate and power. The pro-social justice community is winning because they command the cultural heights within the evangelical world and within the culture at large. This allows them to win out over time without ever having to substantively engage with their opponents’ arguments and positions. As Hunter put it, cultural power is “the power to name things.” It allows the people who possess it to define who the “good guys” and the “bad guys” are, something we see frequently deployed in our society.

The New Calvinist elite won the most critical battle in the persuasion war long before social justice even became an issue. They simply have a much more sophisticated understanding of power and persuasion than their opponents, which is one reason they have been so successful since their emergence as a movement in the mid-2000s. Again, Vermurlen documents many of their savvy moves in his book.

A Fuller Approach to Debate

Discerning and aligning ourselves with the truth is very important. There’s no substitute for truth. We must first have the correct position on issues. This is a very substantive newsletter.

But truth is not self-implementing. Without cultural power and status, and that power’s ability to validate appeals to emotion, the truth very often loses out.

Engaging in debates on the issues of the day requires more than getting the right content and making logical arguments. It must take account of the realities of status and cultural power.

If you have that power, then you probably don’t need my help. If you don’t, if you are stuck in the cultural “periphery,” what should you do?

I can’t do full justice to that topic today. But obviously you either need to acquire cultural status yourself, or somehow reduce the cultural status of your opponents. One strategy for the former was Hunter’s idea of “faithful presence” as described in his book To Change the World. This involves Christians attempting to obtain positions in high prestige, high culture power institutions and affecting the culture in a positive way there. From what I’ve seen, however, this approach has not worked. While many Christians have in fact gotten positions in those organizations, I have not seen them having a cultural impact. In fact, I’ve more often seen the reverse in which seeking elite success causes Christians to converge to secular elite positions over time.

Reducing the status of opponents is not always straightforward, but is possible. It’s can’t generally be done using the same tactics high status groups do to disqualify their opponents, because lower status people and institutions don’t have the power to name things. Various indirect approaches, including humor, trolling or memes, sometimes can work. A small but good example of this is the “preachersnsneakers” Instagram account, which highlights celebrity pastors wearing high priced fashion items. This reframes the high cultural prestige of designer labels as vanity, and puts the spotlight on how some of these people have gotten very wealthy from ministry.

Another approach is to induce the people and institutions with high status to take actions that squander their own legitimacy. The latter has actually been occurring for some time now, even without much inducement. This is shown in the general decline of trust in institutions in our society. To the extent that institutions like the elite media and universities lose trust, they lose legitimacy. They can no longer create real consensus the way the old network news programs could back in the 1980s. They still have immense power, but increasingly they are forced to operate by using that power transparently rather than implicitly and invisibly, which undermines them in the long term. As sociologist E. Digby Baltzell wrote, “Viable civilizations, are, almost literally, clothed in [legitimized] authority; and when the emperor’s clothes are removed his only recourse is the exercise of naked power.” Naked displays of power destroy moral authority and undermine legitimacy.

This is why I believe that declining trust in institutions isn’t the problem, it’s the solution. Anything that drains legitimacy out of the system is a positive at some level. (For institutions we run, the opposite is true. Managing for long term institutional credibility is paramount).

Cultural power also erodes in other ways. Vermurlen shows that New Calvinism is not what it once was, for example. Many of its leading lights like Mark Driscoll, James Macdonald, and Joshua Harris were felled by garden variety scandals (a lesson in itself – the most effective critics of New Calvinism were people like Warren Throckmorton, who focused in on Mark Driscoll and relentlessly dug up dirt about him). Presumably there are more scandals still waiting to come to light. Also, the biggest names in New Calvinism are the proverbial old white guys who represent the past, not the future. Check their names on Google Trends and see that they’ve been in decline for several years. When they exit from the stage, it’s unlikely the next generation will have enough star power to be able to replace them.

We are in a disintegrating, catabolic age. Elite culture power is greater than ever in some ways, but that has sometimes been purchased at a high cost whose full scope is yet to be revealed. What are the long-term consequences of the media abandoning traditional journalistic standards in order to get Trump? We don’t know yet, but they may be profound.

The most important thing to understand is that today it’s generally the quality of cultural power rather than the quality of logical argument that determines which views prevail in society and the church. People who want their position to win out need to make sure they are addressing all the components of persuasion and debate, not just facts and logic.

Coda

The creation of consent is not a new art. It is a very old one which was supposed to have died out with the appearance of democracy. But it has not died out. It has, in fact, improved enormously in technic, because it is now based on analysis rather than on rule of thumb. And so, as a result of psychological research, coupled with the modern means of communication, the practice of democracy has turned a corner. A revolution is taking place, infinitely more significant than any shifting of economic power.

Within the life of the generation now in control of affairs, persuasion has become a self-conscious art and a regular organ of popular government. None of us begins to understand the consequences, but it is no daring prophecy to say that the knowledge of how to create consent will alter every political calculation and modify every political premise.

— Walter Lippmann, Public Opinion