Are You In an Open Network or a Closed Network?

Why you can't easily make it to the top in a closed network without patrons

My previous post on mentorship talked about how a corporate mentor is more than an advisor, but also a patron of your career. I also noted that it was especially important to have this sort of mentor-patron in closed network environments.

I’m following up today with a bit about what I mean by open networks vs. closed networks. I won’t claim to have a rigorous definition, but it’s often something you can sense about a particular environment.

Open Networks vs. Closed Networks

Knowing whether or not you are in an open network vs. a closed network is one of the most important things to understand about the environment where you are operating.

One way to see the difference between the two is to look at proprietary vs. non-proprietary networks. Facebook and Uber are proprietary networks - that is, closed networks. They are controlled by a gatekeeper that decides whether or not you can play. And their algorithms have a huge impact on what you can achieve in them.

Stock exchanges are non-proprietary networks - open networks. You don’t need anyone’s permission to start trading stocks. As long as you play by the objectively defined rules, you are welcome to participate. You won’t get banned for having the wrong political opinions. Nor do you have a network owner who is determined to make sure it not you ends up collecting most of the value out of the system.

I got intrigued by the open vs. closed network idea when listening to venture capitalist and former futures trader Jeffrey Carter apply the concept to cities, particularly Chicago (closed) vs. New York and San Francisco (open). Here’s what he wrote about Amazon’s choice to bypass Chicago for its original HQ project.

Amazon chose Washington DC and NYC. Does it make sense? It all depends on the goals of Amazon. Clearly, they weren’t looking at business decisions like logistics or to make sure their cost of doing business was low. DC and NYC have very high costs of living and very high taxes.

….

NYC on the other hand was a different story. It’s got all the retail capital markets. It’s also a city that is huge, and unlike any other American city. NYC isn’t a closed network. It’s constantly flowing and changing and the question there isn’t “Where are you from?” The question is “Can you do it?” People come from everywhere. There is just a huge number of people there in a concentrated area compared to anywhere else in the US. Networks like that don’t get smaller, they get bigger. NYC is in America, but it doesn’t necessarily feel like an American city. Amazon opened itself up to randomness by selecting NYC.

So, why not Chicago? It’s a big city. It’s logistically perfect. Talent wise, it is super easy to recruit to Chicago. There is not only tech talent, but marketing and logistical talent. That seems to be the stuff Amazon needed….Chicago is a great city. It’s beautiful. The quality of life is wonderful. It has great restaurants. It has really great people with Midwestern values that are loyal. But, it’s not NYC. It’s also not like San Francisco.

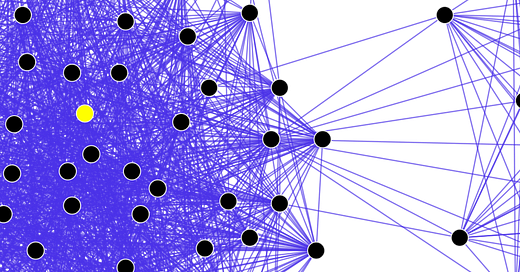

Chicago is a closed network. Look at the 600 member committee that was tasked with bringing Amazon here. See anyone that isn’t connected to anyone? See any looseness around it? It’s the same names in Chicago over and over again. The same people and they all get connected back to the Democratic political machine which is suffocating growth in Illinois and the city of Chicago.

Great gains are not planned or linear. They jump all graphical lines. They often are accidents. That doesn’t happen in tightly controlled networks. Closed networks like predictability, not randomness.

One of the most important characteristics of closed network environments like Chicago is that you need a patron to gain entry to and move up in the network. The title of one of the greatest books about Chicago politics sums up the local attitude perfectly. It’s called We Don’t Want Nobody Nobody Sent. The phrase comes from Abner Mikva’s first attempt to get into Chicago politics:

One day in 1948, energized by the candidacy of Paul Douglas, Mr. Mikva presented himself at the 8th Ward Regular Democratic Organization headquarters. “I came in and said I wanted to help,” Mr. Mikva told historian Milton Rakove. “Dead silence. ‘Who sent you?’ the committeeman said. I said, ‘Nobody.’ He said, ‘We don’t want nobody nobody sent,’” a phrase Rakove took for the title of his oral history of Chicago politics.

By contrast, Silicon Valley is an open network. Clearly, relationships, patron-client relationships, etc. matter a lot there. But the network is permeable. As Carter says, the question is much more “Can you do it?” than “Who do you know?” NYC is similar. It’s a very competitive market, but an open one.

I don’t think it’s any surprise that when I entered the public policy and journalism worlds, I had more success in New York than I did in Chicago, even though in theory New York is a higher level city and thus you might naively think it’s tougher to break into.

The same is true of firms. Accenture, at least when I was there, was a closed network. I believe that’s true in general for professional services firms. If you don’t have a powerful patron in one of those environments, you are not likely to rise high in your career. Having spent so long in that world, I’m very attuned to that, hence my previous article on the topic.

I have much less personal experience in Silicon Valley, but reputedly it is much more of an open network on the employer side too. People bounce around a lot. You aren’t locked into a promotion path within a single firm. If you’re good, you can go raise money for your own company, etc. Back in the day, there used to be a lot of collaboration between firms too. People who worked for competing companies would call each other up for help solving problems. Though I gather has greatly diminished, it was a key part of the early ethos that established the Silicon Valley system.

The Value of Open Networks

Closed networks are great for those who control them or who are at the top of the status hierarchy within them. They are positioned to extract significant money and value out of the network. They are often not so great for most others.

Open networks in general seem to be superior to closed networks. Areas dominated by patron-client relationships, an indicator of closed networks, like Southern Italy are famously backward. As Carter notes, open networks are open to the new, which gives them superior adaptability. They are open to the serendipitous. There’s a reason Nassim Taleb uses Silicon Valley as an example of an “antifragile” system.

In open networks, your position within it is often of secondary importance to the value of the overall network itself. So people in open networks are more generous. They will contribute to build up the overall value of the network. They are willing to give before they get.

You see this behavior in most smaller city technology communities. They are trying hard to ignite their own mini-Silicon Valley ecosystem, and know that it’s actually that ecosystem as a whole that produces the proverbial “flywheel” of growth, not the success of any one individual firm or person (although those successes are important too).

The power of open vs. closed networks is most powerfully demonstrated in UC Berkeley professor AnnaLee Saxenian’s book Regional Advantage: Culture and Competition in Silicon Valley and Route 128. In it she shows that while Boston’s Route 128 corridor started out as America’s top tech hub and had many advantages over Silicon Valley, the latter displaced it because its open network proved far superior to Boston’s closed network in adapting to new technologies and business practices.

Another great example is found in Sean Safford’s dissertation “Why the Garden Club Couldn’t Save Youngtown.” He shows how the open networks of Allentown, Pennsylvania helped it to better navigate the collapse of its steel industry than Youngstown, Ohio was able to do with its closed networks.

Evangelicalism Is a Set of Closed Networks

How does this apply to some of the topics I ordinarily write about, such as the future of the evangelical church? I’m glad you asked.

My impression is that much of the evangelical world functions as a set of closed networks. Let’s use the New Calvinist movement as an example. It was built out of a collection of big name pastors, who are the equivalent of the partners in a professional services firm. One of its key functions, as noted by sociologist Brad Vermurlen, is gatekeeping, a signal that we are talking about a closed network. Basically you need a high level patron within this network to gain access and to rise within it. These relationships seem to operate in a patron-client mode, where the clients are expected to be loyalists. Most of the value of the New Calvinist movement accrued to the people at the top. And we see that the movement is in decline because of its inability to absorb new talent, ideas, etc. It was not open to serendipity and randomness. New Calvinism is thus like Chicago or Route 128, not New York City or Silicon Valley.

The fact that evangelicalism is a set of closed networks is a major problem for its ability to adapt to what I’ve called the negative world, which is today’s cultural environment.

It also poses challenges for any newcomers who don’t have patrons in this system. Consider, for example, the pastor and theologian James Wood, whom I’ve mentioned before. He’s a Millennial, who started multiple churches in Austin, has a PhD in theology, was an editor at the high tone journal First Things in New York, and is a model of the winsomeness so many people advocate for.

In an open network, talent like Wood would be recognized, get backing, etc. In a closed network, Wood is viewed as a threat. Because he’s not a loyalist client of an incumbent elite, he is going to have trouble rising in the system. Which is a shame, because people with profiles like this are exactly who the evangelical world should be looking to build up as next generation leaders. Or at least to give them a chance to show their stuff on the big stage.

This also affects me. Although my work has concentrated on evangelicalism’s future and men’s issues within it, I also don’t have any elite patronage in that world. Make no mistake, this is definitely an inhibitor of what I’m trying to accomplish.

In my mission update report, I noted that I’d like to build my free subscriber base here to 50-100,000 people. With the right patronage, that would be trivial. At a minimum, the right patronage could signal boost me a lot.

Without that patronage, I have to build up my audience by other means. It’s no accident that the person who has grown my exposure the most was Rod Dreher (Eastern Orthodox), and that the most influential and widely read piece I’ve written was published in First Things (a Catholic run publication). Fortunately for me, I also have good networks in the public policy world, social media, and both conservative and mainstream media. (Interestingly, I would classify the mainstream media as an open network today, which is why I get quoted in places like the New York Times). I did manage to find a high quality major evangelical publisher in Zondervan for my forthcoming book.

One of the reasons I have that subscriber goal, by the way, is that there’s a second route to entering this world other than patronage, which is to have entrepreneurial success in building a large audience. The classic example is the charismatic church planter who builds a hot new megachurch. My plan is to find an alternate path to becoming too big to ignore and get my message out, because what I have to say is important.

In Conclusion

Since I seemed a bit negative towards closed networks, I’d be remiss if I didn’t point out that Accenture, which was a closed network when I worked there, has been extremely successful. Professional services firms seem to make closed networks preform at a high level. I’m not sure why this is, though I’m sure scholars have studied it.

For you, it is critical to understand whether you are in an open or closed network environment. If it’s the latter, then finding a patron is even more important than in the ordinary case.

The publishing world is an interesting example.

Mainstream traditional publishing is very much a closed network, you have to go through the gatekeepers, stick to the script etc.

But the explosion of indie and self publishing has created a parallel open network which allows much more open access, innovation etc.

It's particularly interesting because a lot of authors end up building a hybrid model of both in order to reap some of the rewards of each.

It also seems like closed networks are more susceptible to corruption. Both Chicago and Southern Italy which you mention here are famously corrupt, but I can think of other examples. Perhaps when who you know becomes the most important factor in your success, then favors emerge as currency.