The Trouble with Childhood Trauma

Rob Henderson's powerful memoir of family breakdown, foster care, and America's social status system

Audio version of this article (AI generated)

It’s a truism that having kids gives you a new perspective on childhood. My son is seven years old. He’s never missed a meal in his life. It occurred to me that the idea that there might not be food to eat when he’s hungry has probably never entered into his head. Similarly, he’s probably never even imagined that his mother and I wouldn’t be there, that he might be taken out of our house and dumped somewhere he’s never been to live with people he’s never met.

As we age, we learn, both intellectually and through experience, that the world is full of terrible things, and that pain and suffering are an unavoidable part of the human condition. Even as adults, some experiences are so traumatic that their effects linger for years or even for the rest of our lives.

When these things happen to young children, so-called “Adverse Childhood Experiences,” it can distort their development and permanently damage them and their prospects in life because they don’t have the mature resources necessary to cope with what has happened to them. In a sense, even if they “overcome” these experiences, they never truly leave them behind.

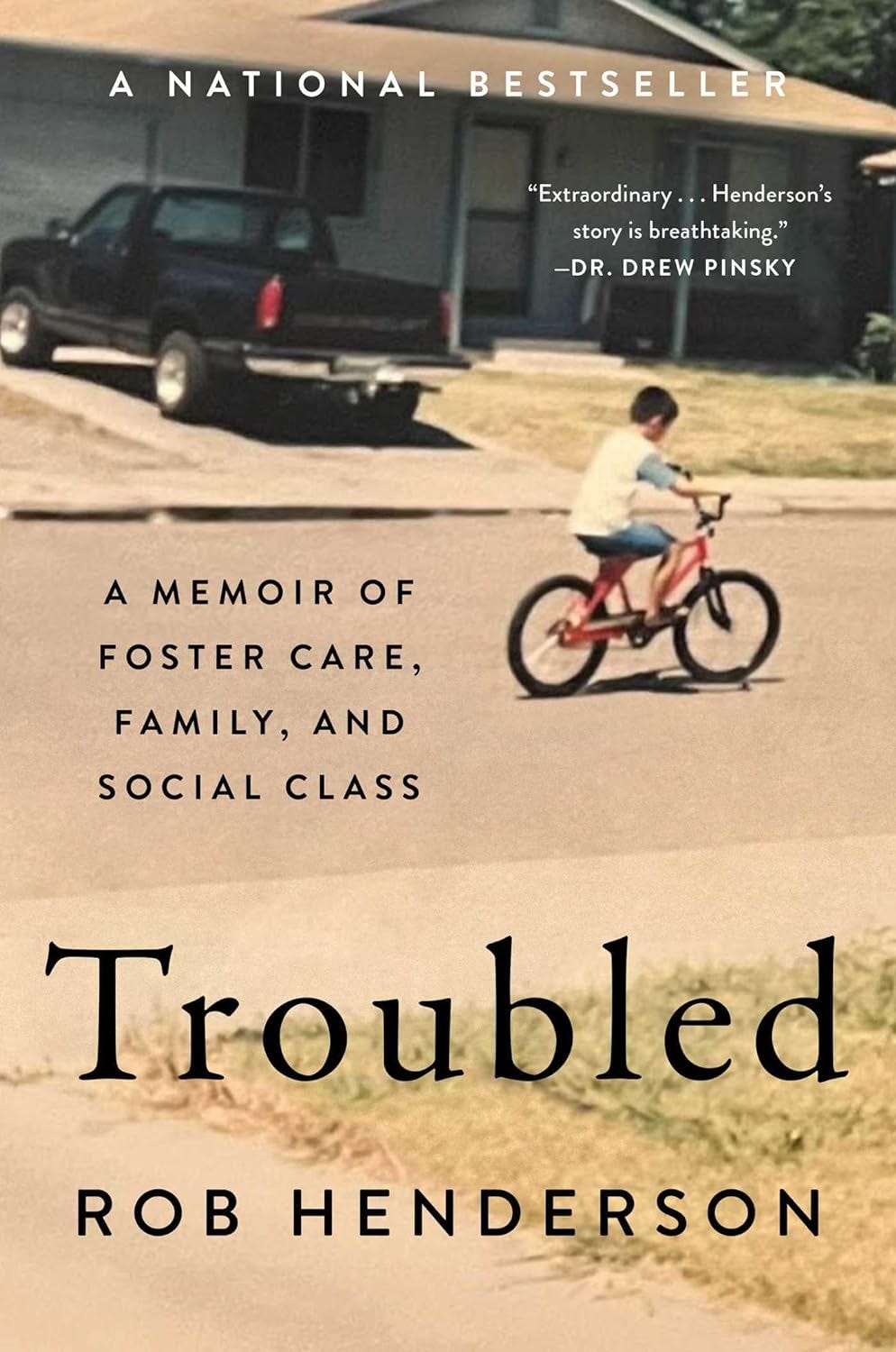

Rob Henderson’s memoir Troubled: A Memoir of Foster Care, Family, and Social Class addresses the reality of how unstable environments permanently hurt children. It’s an especially good read because Henderson not only grew up in such a troubled environment, but is also a Ph.D. psychologist from Cambridge University. You may have noticed that I frequently link to his work, and he has one of the best Substacks out there. Thus he has a mix of compelling personal experience, and the intellectual ability to put this into a social science and cultural context.

Henderson’s life is a case study in crazy. He never met this father, after whom he was named. Later, he learns through a DNA test that his father was Hispanic. His mother was Asian, and deeply troubled, with a serious drug problem. She had already had two other children with two different fathers when he was born, half-brothers he has never met. Henderson was taken away from her and put into a foster care, where he rotated through a series of foster homes.

Here was one such experience:

Months later, Gerri, my social worker, came to the house. It was time for me to go live somewhere else, she said. I’d just turned seven, and this time I didn’t cry. I was dejected, but the tears didn’t come. I’d learned to shut down, sealing myself off from my emotions. Gerri helped me gather my clothes and put them into a black garbage bag. She picked up a shoe box next to my bed, and a bunch of cards fell out…We packed up and walked out to her car. I wondered if this was how the rest of my life would be: moving to a home, staying for a while, and Gerri putting me somewhere else. By this point I knew that other kids didn’t have to do this.

I previously served on the board of Court Appointed Special Advocates (CASA) for Children of Cook County, Illinois. CASA trains volunteers who serve as special advisors to the judge in cases of children who are involved in the juvenile justice system on account of parental abuse or neglect. These children have done nothing wrong themselves, but are merely unlucky to have messed up parents and home life. Since social service case workers are typically overloaded, and pretty much everybody involved in the case has their own personal interests at stake, CASA volunteers spend time learning about the case and the child and are chartered with acting as advocates for the best interests of the child to the judge.

During our initial board training, someone came into the room and gave us black garbage bags. We were told to put all of our possessions in that bag, and come with her to a place we didn’t know and had never been.

For us, we knew the reality of what was happening, so it didn’t really affect us all that much truth be told. But reading about Henderson’s experience took me back. Imagine being a small child, and a government case worker comes into your bedroom out of the blue and tells you to put everything you own in a black garbage bag and bring it to some strange new place. Unless it actually happened to us, we can’t really relate to that. Children without our intellectual and life perspectives experience these things in completely different ways that we might think they do:

Children believe that if a family loves them, then that family won’t let them be taken away. Adults understand on an intellectual level that this isn’t true—the foster system works the way it works—but little kids don’t fully grasp this.

This happened many times to Henderson, who I believe lived in about seven different foster homes, some of which were candidly exploitative of him. As it put it:

I’ve met some well-heeled people who have attempted to imagine what it’s like to be poor. But I’ve never met anyone who has tried to imagine what it would have been like to grow up without their family.

Being in foster care puts a kid into pretty much the highest risk category in life you can be. Of boys, Henderson notes:

Studies indicate that in the US, 60 percent of boys in foster care are later incarcerated, while only 3 percent graduate from college. What this means is that for every male foster kid like me who obtains a college degree, twenty are locked up…Even when you present opportunities to deprived kids, many of them will decline them on purpose because, after years of maltreatment, they often have little desire to improve their lives.

Later, he was adopted by a family in a redneck area of California north of Sacramento, where he transitioned to a somewhat more stable working class milieu of the type I grew up in. His last name comes from this adoptive family.

But more stable doesn’t mean stable. His adoptive parents divorced. To try to hurt the mother, his adoptive father afterward refused to see Rob while still having many visits with own older biological daughter. His adoptive mother comes out as a lesbian and ends up in relationships with multiple different women. One of them lasted a significant period of time and seemed to offer the hope of a stable family life, but a freak accident lead to a large insurance settlement that ends up destroying that too. The money was invested into real estate right before the housing crash, leading to foreclosures and the ultimate end of that domestic partnership.

Despite engaging in high risk activities, Henderson manages to avoid blowing up his life during high school, something many of his friends could not pull off. Reflecting back on my own life, I see a few factors at work here. The first is good fortune - there but for the grace of God go I. The second is that Henderson’s high IQ allowed him to understand that some risks were just too insane to take. The third is that authorities around him like teachers recognized that he was very smart and had potential, and so probably cut him some slack on that basis (maybe even to a greater extent that he himself realizes).

After high school he enlists in the military, which, JD Vance style, helps him get on track in life - though the problems of his childhood follow him there. This episode is an interesting look at what the military experience can be like for young people.

While his enlistment is winding town, he finds out about Yale and ends up getting in, an episode with something of a deus ex machina quality. Yale is where Henderson starts developing the thinking that got him known, his analysis of social class and “luxury beliefs.”

He talks about the bewildering and seemingly self-contradictory social world in which he found himself at Yale:

I learned a term I’d never heard before: fat shaming. It was remarkable that students who seldom consumed sugary drinks and often closely adhered to nutrition and fitness regimens were also attempting to create a taboo around discussions of obesity. The unspoken oath seemed to be, “I will carefully monitor my health and fitness, but will not broadcast the importance of what I am doing, because that is fat shaming.” The people who were most vocal about what they called “body positivity,” which seemed to be a tool to inhibit discussions about the health consequences of obesity, were often very physically fit.

And:

Many of my peers at Yale and Stanford would work ceaselessly. But when I’d ask them about the plans they’d implemented to get into college, or start a company, or land their dream job, they’d often suggest they just got lucky rather than attribute their success to their efforts. Interestingly, it seems like many people who earn status by working hard are able to boost their status among their peers even more by saying they just got lucky.

And:

Prestigious universities encourage students to nurture their grievances, giving rise to a peculiar situation in which the most advantaged are the most well-equipped to tell other advantaged people how disadvantaged they are.

Gradually, he develops his concept of luxury beliefs, which he defines as “ideas and opinions that confer status on the upper class at very little cost, while often inflicting costs on the lower classes.”

As with the fat shaming example above, American elites largely promote libertinist practices that they themselves avoid, or have the familial resources to at least mitigate the risks of. Henderson is scornful of the way these elites promote self-destructive behaviors to people in the lower classes:

The luxury belief class claims that the unhappiness associated with certain behaviors and choices primarily stems from the negative social judgments they elicit, rather than the behaviors and choices themselves. But, in fact, negative social judgments often serve as guardrails to deter detrimental decisions that lead to unhappiness. In order to avoid misery, we have to admit that certain actions and choices are actually in and of themselves undesirable—single parenthood, obesity, substance abuse, crime, and so on—and not simply in need of normalization. Indeed, it’s cruel to validate decisions that inflict harm, especially on those who had no hand in the decision—like young children.

He sees a direct path from the luxury belief system to the social structures that promote the kinds of destructive behaviors that inflicted suffering on him.

We now live in a culture where affluent, educated, and well-connected people validate and affirm the behaviors, decisions, and attitudes of marginalized and deprived kids that they would never accept for themselves or their own children. And they claim to do this in the name of compassion. It’s fine if Antonio and I skip class and ruin our futures, but it’s definitely not fine if their kids do so. Many of the people who wield the most influence in society have isolated themselves and their children from the world I grew up in, while paying lip service to the challenges of inequality.

In the past, the high status might have differentiated themselves through conspicuous consumption of products unavailable to the common man. There’s still some of that, but increasingly today the high status differentiate themselves by the lingo and the beliefs they hold, beliefs too costly for ordinary people to hold.

These beliefs, and the way they are expressed, are also constantly changing, to continually put new distance between the elite and the rest. It’s difficult for people with lower IQ who are not embedded into an elite milieu to imbibe and keep up with this constantly shifting status landscape. He gives an example of this constant churn using an old school consumption item: the Broadway musical “Hamilton.”

This reveals how social class works in America. It is not a coincidence that when Hamilton tickets were prohibitively expensive, affluent people loved it, and now that it can be viewed by ordinary Americans, they ridicule it. Once something becomes too popular, the elites update their tastes to distinguish themselves from ordinary people.

Henderson is one of the best at putting the high status world under a microscope. In addition to his compelling life story, this alone makes the book, and his Substack, worth reading.

You might think Henderson “made it,” that he overcame his background to find the American Dream. There’s a sense in which this is true, but perhaps the most important message of the book is that no amount of educational and material success can compensate for the things he experienced, particularly the lack of a stable family. He says:

I’ve come to understand that a warm and loving family is worth infinitely more than the money or accomplishments I hoped might compensate for them.

…

External accomplishments are trivial compared with a warm and loving family. Going to school is far less important than having a parent who cares enough to make sure you get to class every day.

He would trade his elite success for the healthy childhood did didn’t have and the family relationships he will never possess:

I’ve heard variations of the phrase “I’m grateful for what I went through because it made me who I am today.” Despite what I’m proud to have accomplished, I strongly disagree with this sentiment. The tradeoff isn’t worth it. Given the choice, I would swap my position in the top 1 percent of educational attainment to have never been in the top 1 percent of childhood instability.

He reminds us that the real problem with childhood trauma isn’t the downstream consequences in terms of education and income, but rather the trauma itself.

Childhood trauma isn’t bad because it leads to lower graduation rates or lower incomes. It isn’t bad because it leads to higher rates of addiction or crime. It’s bad because of the firsthand, phenomenological experiences of the kids going through it. In other words, it’s bad because it’s bad.

Sobering words.

Rob Henderson’s Troubled is a great companion to economist Melissa Kearney’s book on the two-parent privilege, one that brings the human side of the statistics to life. Highly recommended.

Because of circumstances, I am the person that Rob Henderson has never met: I grew up in a happy, well-adjusted family and I have had to imagine what it would have been like to grow up without my family.

My wife and I adopted four children from foster care; all four are biological siblings who have largely grown up together (for the most part, they were kept in the same foster homes). When we took them in, they were 11, 9, 8 & 7. They had (and continue to have) very real memories of their trauma.

When most people who had a happy childhood become parents, they largely adopt the parenting style that their parents used on them. We adjust it for aspects that we didn't particularly care for, but it gives us a good template for how to do it. I was not able to do that; it would not have worked. Almost every parent takes for granted that their child trusts them. Even when my parents angered me or disappointed me, I never doubted in my heart of hearts that they loved me and wanted the best for me. I believe this to be true for almost every biological parent/child relationship. But my relationship with my kids took a long time to develop into that. My children were taken from a neglectful home and placed in the care of various people who were paid to care for them. The best way to describe a foster parent is that they are a caretaker; even the best ones, who are doing it for the right reasons, are still just paid help. So the children cannot trust them the way that a child trusts a parent; it's the difference between a shepherd and a hireling in John 10. I had to resolve to be extra-careful to not make promises that I could not guarantee I would keep; my word had to be my bond in order for my kids to ever trust me.

The trauma of childhood is real and it is enduring. My oldest rarely trusts someone when she first meets them. She assumes that anyone she becomes attached to will abruptly leave her life and she will often pre-emptively cut them out of her life so the pain comes on her terms. This is a terrible habit that she must break in order to have strong, healthy relationships as an adult, but I cannot blame her for developing it as a defense mechanism. Imagine living with a foster parent you like and then one day, a worker comes with the black bag. You have no say in the matter. It is the equivalent of having a boss that you love and one day, HR comes into your office and says you are being transferred to the Cleveland branch. Box your things. Now. You don't think that would impact your future relationships with co-workers?

And this trauma manifests itself in my kids with a defeatist attitude toward life. As a kid, when I faced bad news at school--like an impending bad grade--I would find a million ways to attack it to get the grade up. I would seek out extra credit. I would ask for grace to turn in a missing assignment or to redo one that I did poorly on. Until the report card was actually printed and sent to my parents, I would try anything that I thought would help me improve the grade. My parents instilled in me a sense that you try everything and the worst thing anyone can say is no. But when my kids face the same situation, they give up. I have to push and prod and force them not to give up. It drives me bonkers. But then I think about the black bags. When the CPS worker tells a child that they are moving that night, there is nothing a child can do to change it. There is no way around the bureaucracy. "This is going to happen whether you like it or not" is a message that a child should sometimes hear, but it should never be the overwhelming message of their lives. But that is what a child always hears in foster care. "This decision has been made without your input by people for whom you are a case number" is such a destructive message to internalize.

Watching the trauma my children endured has made me way less likely to call CPS on another parent. The foster care system is a necessary evil. It is evil to take children from their biological families and pay caregivers to serve as substitute parents. It inflicts lifelong traumas. But it is necessary because there are instances where it is less evil to do that than it is to have children be sexually abused, exposed to illegal drugs or left dirty and starving. So I will not call CPS unless I suspect that the evil the child is enduring at home is worse than the evil of ripping them from their parents. The people who call CPS because a 14 year old is a latchkey kid for a few hours while his mom works have never once considered the evils and traumas of foster care.

My experience really made me consider how much my family made me who I am and who I would be without it. My father and my grandfathers both taught and exemplified the basic attributes of a man: be reliable, be trustworthy, give an honest day's work for an honest day's pay, faithfully love your wife and contribute to the community. Had I grown up in an unstable environment, my talents and abilities would be the same, but I have serious doubts about my ability to be reliable and faithful.

I was not in a situation as bad as Henderson's, but I echo his views on trading for a functional childhood. And oddly enough, the older I get, the more I dwell on/see the effects of an abnormal childhood.

And an abnormal childhood is now the majority experience in America, to one degree or another.